2.3 Realism

We all learn more over time. We can be cautiously optimistic that we will know more in the future than we know today, rather than falling into a cynical attitude that ŌĆ£no one will ever knowŌĆØ the answer to a question just because it is complicated or difficult.

Persistence despite frustration and failure is an intellectual virtue. At the same time, we should avoid excessive idealism about the future, and recognize that there may be things we could only understand after we have learned much more than we already know. We should avoid simplistic answers and develop the virtue of intellectual patience. When formulating theories about the world, we should strike a balance between seeking comprehensive theories that explain as much as possible, and simple theories that have as few explainers as possible.

2.3.1 Tempered Optimism

Intellectual progress is slow and takes effort.

The Vice of Trusting the Inevitability of Progress

It is exciting to see how much progress the sciences have made over the last few decades, or the ways in which life is easier and more pleasant for people in some societies than it was for their ancestors as a result of technology. The internet makes it easy for people to quickly look up commonly accepted information, when they might have previously engaged in painstaking library research. There are many reasons to be optimistic about the progress of knowledge.

Excessive optimism, however, can lead someone to conclude that intellectual progress in every area is inevitable, that if we donŌĆÖt understand it yet, we will understand it soon. For instance, someone might speculate that scientific methods will resolve (or have already resolved!) all of the difficult philosophical questions, or that the internet will make education obsolete, or that computer calculations will eventually relieve humans of having to bear moral responsibility for their choices. ThereŌĆÖs no need for you or I to do any difficult thinking, because eventually, someday, somebody else will have all of the answers for us.

There are two problems with this kind of speculative optimism. First, it ignores that intellectual progress only happens when people like you and I are actively engaged in that process. Second, more subtly, it ignores that some questions do not have the kinds of answers that someone can ever test in a lab, or calculate with an algorithm, or look up an answer to on google. It ignores that faster processing speeds might make it easier to solve mathematical equations, and faster data speeds might make looking up some information quicker, but speed alone wonŌĆÖt solve many of the more difficult problems that we face. In these cases, optimism needs to be tempered with realism.

The Vice of Giving Up Too Soon

At the same time, the opposite attitude, assuming that there can be no progress, is also a vice. ŌĆ£WeŌĆÖll never knowŌĆØ is an easy refrain for someone to fall back on when they simply donŌĆÖt want to deal with a complex and difficult question. Thorny philosophical, ethical, or political debates can get discouraging and seem hopeless. Someone who feels overwhelmed by these debates or anxious about them may want to ŌĆ£bury their head in the sandŌĆØ, or ignore or shut down the discussion, hoping it will simply go away.

If you feel like giving up, try to imagine a time in the past when someone might have said that a problem was beyond our capacity to understand, unknowable, or unsolvable, but we now do know the solution to that problem today. Imagine trying to explain how contagious diseases work, for instance, to somebody who canŌĆÖt fathom microscopic viruses or bacteria in the water or air. For some of the questions that right now lead us to say, ŌĆ£we can never knowŌĆØ, there could be some person in the future who does know, and who could explain it to us. While being realistic about the limits to our knowledge, we can also be optimistic about the capacity of our minds to grow and develop to solve new challenges, and to keep pursuing answers as best as we can.

An attitude of being optimistic, but also realistic, about the potential for the future progress of our knowledge, helps avoid both our tendency to give up too early when a question is difficult, but also our tendency to rest on the speculation that it will be inevitably solved.

2.3.2 Patience

The echidna is a mammal which lays eggs.

The Virtue of Intellectual Patience

Thinking quickly is often confused for intelligence. In fact, someone who thinks slowly and methodically is the most likely to make valid inferences and avoid fallacious reasoning. Intellectual patience involves slowing down the process of reasoning, taking it step-by-step, to make sure that one doesnŌĆÖt jump to conclusions. By default, we tend to think in terms of general categories. Every cat I see provides me with information about cats in general, and every cat I encounter I interpret through the lens of what I already know about cats. Intellectual patience helps someone recognize the possibility of exceptions. Maybe this cat isnŌĆÖt typical of cats: letŌĆÖs wait and see.

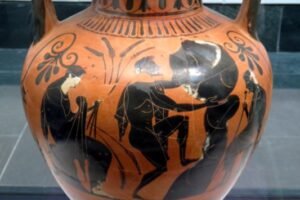

Hasty Generalization

The fallacy of Hasty Generalization occurs when we form a generalization based on too little information, or too few examples. A ŌĆ£generalizationŌĆØ is a claim about what holds universally (for every or all cases), or a claim about what holds generally (mostly, usually, or typically), or a claim about what never holds (in no cases). Since generalizations include cases we havenŌĆÖt seen, justifying a generalization requires significant evidence. Even generalizations with a great deal of evidence turn out to be false: before the discovery of the platypus and the echidna in Australia, which are both mammals that lay eggs, people living outside of Australia would have thought ŌĆ£No mammals lay eggsŌĆØ was true.

Our brains are always searching for patterns, and using them to try to predict what we will see next, and so we have a tendency to want to accept generalizations prematurely. Before making a generalization, itŌĆÖs best to slow down and consider how much of the whole picture your evidence actually represents, or whether the examples youŌĆÖve been exposed to are not typical. Below are two examples of hasty generalization:

- I know College students who abuse alcohol.

- Everyone else I know knows College students who abuse alcohol.

C. Most College students abuse alcohol.

- Sarah is not lonely.

- Malik is not lonely.

- Erlene is not lonely.

- I am lonely.

C. Nobody but me is lonely.

The Fallacy of Accident

The converse of the hasty generalization is called the fallacy of accident (the word ŌĆ£accidentŌĆØ here means something like ŌĆ£random exceptionŌĆØ). Instead of being too quick to generalize based on too little evidence, the fallacy of accident involves a case where someone is too quick to apply a generalization to cases where it doesnŌĆÖt apply. Recall that some generalizations are true most of the time, but not all of the time. ŌĆ£Mammals give live birthŌĆØ is a true generalization, because most mammals do give live birth. If we donŌĆÖt slow down, however, we may miss that weŌĆÖre dealing with the exception to a generalization: the echidna and the platypus do not give live birth. Two more examples:

- Birds fly

- Ostriches are birds.

C. Ostriches fly.

- Children who are crying often need hugs.

- Olivia is a child who is crying because she has a really bad sunburn.

C. Olivia needs a hug.

Remember to slow down! While weŌĆÖre trained by timed tests in elementary school to regard ŌĆ£quick thinkingŌĆØ as the same as intelligence, often slow thinking is more likely to be right.

2.3.3 Persistence

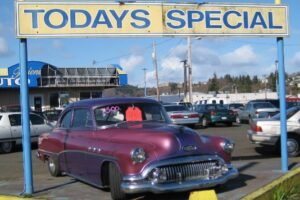

People evaluate whether they got a “good deal” by the first price they see.

The Virtue of Intellectual Persistence

A hard worker is someone who doesnŌĆÖt rush so quickly to finish their task that they make a mistake, but also someone who isnŌĆÖt asleep on the job: they continue diligently with their work until they are finished, even when there is some drudgery involved. A good reasoner is like a hard worker. They have the intellectual patience not to rush or jump to hasty conclusions, but they donŌĆÖt slow down so much that they come to a stop. They keep moving forward and donŌĆÖt settle for short-cuts. This is the virtue of intellectual persistence.

When we lack intellectual persistence, perhaps because weŌĆÖre tired and just want the solution to our problem, already, then we tend to settle for easy but inaccurate answers. There are many ways in which someone can settle too soon on an answer, but weŌĆÖll discuss just two here.

The Dictionary Fallacy

The ŌĆ£dictionary fallacyŌĆØ is a common fallacy for college students who were taught in their previous schooling to make use of dictionaries to look up unfamiliar words. Dictionaries are very useful in college too, of course, but dictionaries do not contain much information about the world: dictionaries just help someone understand the social conventions for using a word. Dictionaries do not settle any debates except for debates about word usage. For instance, this would obviously be a fallacy:

- The dictionary defines ŌĆ£climateŌĆØ as ŌĆ£The usual condition of the temperature, rainfall, wind, pressure, and humidity.ŌĆØ

- The dictionary defines ŌĆ£changeŌĆØ as ŌĆ£To make or become different from the usual condition.ŌĆØ

- ŌĆ£Climate changeŌĆØ is a contradiction.

- Contradictions are impossible.

C. Climate change couldnŌĆÖt possibly happen.

The Anchoring Effect

Many of us have learned that the first paragraph and last paragraph of a paper, or the beginning and end of a speech, are the most important parts of the speech. The first day of a class sets the mood for the class, and the first impression of a person influences the way we continue to evaluate that person. This is the result of a cognitive bias which psychologists call the ŌĆ£anchoring effectŌĆØ.

Because of the anchoring effect, the first bit of information which we get about something becomes the standard against which we weigh other information, even if the first information was arbitrary or random. For example, the first price that someone is quoted on the purchase of a new car is the standard they use to determine later whether or not they are getting a ŌĆ£dealŌĆØ, even if the initial price was random, and the price they ŌĆ£negotiateŌĆØ is in fact the market price of the car.

Even when the initial anchor is absurd or irrelevant, it can influence our judgments. For instance, one group of people were asked whether Gandhi died before or after age 9, and a second group were asked whether he died before or after age 140; both are absurd numbers, and all respondents answered correctly. Both groups were then asked to guess how old they thought Gandhi was when he died. The first group estimated on average that he died at age 50, and the second group that he died at age 67.

Our own intellectual laziness is what allows the anchoring effect to be so influential. While none of us consciously chooses to be influenced by the anchoring effect, we do have a choice about how critically we evaluate our own guesses and estimates. We can still easily recognize that neither the ŌĆ£first wordŌĆØ nor the ŌĆ£last wordŌĆØ should have more weight than the middle. We give extra weight to the first (and last) information we get in part because it is mentally so easy. In fact, one thing we know from studies is that the anchoring effect is strongest when people need to come up with a guess or estimate quickly, with minimal effort.

Intellectual persistence means resisting short cuts, whether itŌĆÖs appealing to the easiest-to-access source (the dictionary) as an authority, or whether itŌĆÖs using the easiest-to-remember information (the first thing we heard) as a standard of assessment. Thinking can sometimes take a lot effort, but it can also pay off (remember that when you go to buy a car).

2.3.4 Simplicity

“It all depends on how you define ‘speeding’, officer.”

Vices of Insufficient Simplicity

Recognizing and valuing simplicity is an intellectual virtue. Simplicity in our theories and in our language help us more clearly understand the world. There are a number of ways in which people can lack sufficient appreciation for simplicity, and be reasons they might be tempted instead to choose complication for the sake of complication. On this page, we will explore two ways in which two things might need to be simplified:

- Theories could need to be simplified, when they create more explanations than needed (it Fails OccamŌĆÖs Razor)

- Theories could need to be simplified, when they obscure the main explanation (Overcomplication)

- Language could need to be simplified, when it creates more meanings than needed (Distinctions without a Difference)

- Language could need to be simplified, when it obscures meaning (Obscurantism)

Failing OccamŌĆÖs Razor

Named for the Medieval philosopher and Franciscan friar William of Occam, the principle of ŌĆ£OccamŌĆÖs RazorŌĆØ states that, all other things being equal, the simpler of two competing theories is to be preferred. OccamŌĆÖs razor is an expression of the intellectual virtue of appreciating and valuing simplicity, or not desiring complication for complicationŌĆÖs sake.

This does not mean that the ŌĆ£simplest theory is always rightŌĆØ. In fact, simplistic explanations are often wrong: it might be simpler to believe that there is only one virus in the world with different effects on people, rather than hundreds of thousands of viruses each with their own effects on people, but the ŌĆ£one virusŌĆØ theory, while very simple, would fail to explain other things (like immunity to some but not all viruses). Rather, what it means is that, if we have two equally good ways of explaining something, we should default to the simpler rather than the more complicated explanation.

OccamŌĆÖs Razor is a principle which is often invoked in scientific and philosophical reasoning, but you also probably make use of it everyday. For instance, suppose that there are two explanations for why youŌĆÖve run into a traffic jam on the road. One explanation is that there was one traffic accident. The other explanation is that there were two traffic accidents. Of course, there might have been two traffic accidents (coincidentally), or there might have been no traffic accident (the traffic jam might be caused by political protesters). Both of those are possibilities. But one traffic accident is more likely than two, and more likely than none. So, a single traffic accident is the simpler explanation of the traffic jam.

Overcomplication

First, people confuse complication for comprehensiveness, or miss the point because they are overcomplicating things. A comprehensive account of something — that is, an account which explains all of the relevant causes — is inevitably going to be complicated, because most events have many causes. Any attempt at a comprehensive explanation why a particular individual has heart disease, or why voters made the choices they did in a recent election, or why two countries are at war, is going to be complicated. It is a fallacy, however, to conclude the reverse: that any complicated account of something is therefore comprehensive.

Imagine that someone wrote a 100-page explanation of a patientŌĆÖs heart disease, without mentioning the patientŌĆÖs lack of exercise. Or, imagine that someone wrote a lengthy doctoral dissertation on voting behavior, without mentioning the candidates running for office. Or, imagine that someone produced a documentary about the causes of a war which focused entirely on cultural differences, rather than military strategy or economic interests. It is possible to give a very long, complicated explanation of something, without fully explaining it, or even without explaining the most significant element. The most significant cause might in fact be the simplest and most straightforward one.

Distinctions without a Difference

Second, people confuse complication for precision. Someone can try to draw ŌĆ£distinctions without a differenceŌĆØ, to claim that two things are relevantly different because of some subtle difference in wording or meaning. Although it is a useful skill to be able to notice subtle differences in wording or meaning, and to use words precisely, these differences are not always relevant to the situation at hand.

For instance, someone might claim that one word has multiple meanings which are only subtly different from one another, as expressed in Bill ClintonŌĆÖs famous statement, ŌĆ£it depends what the meaning of the word ŌĆśisŌĆÖ isŌĆØ. Trying to get out of a traffic ticket, someone might say, ŌĆ£It depends what you mean by ŌĆśspeedingŌĆÖ, officer. Do you mean ŌĆśspeedingŌĆÖ as in going fast relative to the speed limit, or ŌĆśspeedingŌĆÖ as in going fast relative to other drivers?ŌĆØ (This is not an effective way to get out of a traffic ticket.)

Another way to draw a distinction without a difference is to claim that because two words are different, there is a meaningful difference between them. For instance, suppose that the university has pledged not to raise tuition. It then announces that ŌĆ£Unfortunately, to avoid raising tuition, it will be necessary to increase student fees at a rate of $50 per credit hour.ŌĆØ The administrative distinction between tuition and a student fee may not be a relevant difference for most students. Or again, suppose a compulsive gambler defends his behavior by insisting that, ŌĆ£I donŌĆÖt consider my roulette habit to be gambling. It is really more like a risky but potentially profitable investment.ŌĆØ Here the attempt to draw a subtle distinction is irrelevant to the point.

Obscurantism

Lastly, people can confuse complication for intelligence. Complicated things require a lot of mental effort to understand, and so people tend to confuse a complicated statement with a brilliant or intellectual statement. Obscurantism is using ŌĆ£obscureŌĆØ or overly complex language for the deliberate purpose of trying to sound intelligent, while not actually saying much of anything. For example:

It should be obliquely reticent that ameliorating the budget deficit would impermissibly inculcate an atmosphere of illegitimate homogenization in the popular economic milieu, in place of the intransigent synergies overdetermined by the plebeianism of difference-based context-making and the self-selection of the entrepreneurial spirit.

Another example:

Legalizing the sale of marijuana is the shortest circle attainable towards the articulated plateau of resuscitation in the azure history of this gilded, sensory-positive longitude. Well-wishing partisans who reanimate the remains of the subliminal narrative misconstrue their own inadequate proprioceptors on this issue.

Neither statement says anything meaningful or comprehensible. Here, simplicity in language would be more useful for persuading someone through reasoning, rather than through a display of vocabulary.

2.3.5 Comprehensiveness

A recipe is more than just a list of ingredients.

Vices of Excessive Simplicity

While a love of simplicity is an intellectual virtue, a good reasoner should also aim for theories which are comprehensive, which included all of the relevant causes and do not oversimplify reality. Below are three fallacies which can result from an excessive pursuit of simplicity.

Oversimplification

Oversimplification is the fallacy of concluding that because one thing is relevant or necessary, it is the only thing which is relevant or which is needed. Oversimplification is the opposite extreme of overcomplication. For example:

- These french fries need more salt.

C. All these french fries need is more salt.

- This country needs to stop being so divided.

- Patriotism reduces the divisions within a country.

C. All this country needs to stop being so divided is more Patriotism.

Reductionism

Reductionism is the fallacy of concluding that, because two things are closely related, they must be identical, or one is really just the other by another name. Reductionism is the opposite extreme of drawing distinctions without a difference: it is failing to recognize important distinctions. For instance:

- The market value of something in economics is just what others are willing to exchange for it.

C. The value of something is just what others are willing to exchange for it.

The fallacy above confuses ŌĆ£valueŌĆØ (the worth something has to somebody) with ŌĆ£market valueŌĆØ (what other people are willing to pay for something). But many sentimental items have high value to somebody, even though they have low market value. Here is another example of reductionism:

- Every time you think there is electrical stimulation in the brain.

C. Thinking is just electrical simulation in the brain.

Fallacy of the Single Cause

The fallacy of the single cause occurs when someone concludes that one of the many causes of an event was actually the cause, and the only cause. For instance:

- Max got in a car accident because his breaks were worn.

- Texting while driving is not the same thing as having worn breaks.

C. MaxŌĆÖs texting while driving was not a cause of the car accident.

- The availability of guns is not the cause for why anybody commits mass murder.

- If something isnŌĆÖt the cause of an effect, it doesnŌĆÖt causally influence that effect.

C. The availability of guns does not causally influence the frequency of mass murder.

Most events are caused, or causally influenced by, many other things. Rarely is there one single cause for an event. Sometimes, even if something isnŌĆÖt an outright or direct cause of a particular event, it might still be a significant influence or factor on why events of that type tend to happen. So, even if we uncover one important and significant causal factor, that isnŌĆÖt a reason to think that nothing else is a factor, or even it something is not the main or primary cause, that isnŌĆÖt a reason to dismiss it as entirely irrelevant.

Submodule 2.3 Quiz

Licenses and Attributions

Key Sources:

- Watson, Jeffrey (2019).┬ĀIntroduction to Logic. Licensed under: (CC BY-SA).

Next Page: 3.1 Cooperation