2.1 Proper Regard

The three most basic intellectual virtues reasoners should aim to develop involve holding the proper degree of regard for themselves as reasoners, for the truth, and for knowledge. Having too much or too little regard of each type tends to lead to fallacious reasoning.

Having intellectual self-respect is an important virtue, and having too little of it makes it easy to fall prey to appeals to ridicule or false authority. Intellectual Humility is a virtue, too, however, and having too much self-regard can lead to hubris and dismissing legitimate expertise.

Similarly, it is a virtue to have enough desire for the truth that one seeks to be right, but also a virtue to have enough respect for the truth that one is willing to have been wrong.

Reasoners also need to seek a balance between skepticism and credulity, neither desiring knowledge so much that they accept falsehoods as knowledge, nor respecting knowledge so much that they are unable to know anything.

2.1.1 Intellectual Virtues and Fallacies

Aristotle with a bust of Homer by Rembrandt. Oil on canvas, 1653

Intellectual Virtues

In this module, we will study fallacies, or common mistakes in reasoning which people have a tendency to make. We will also study the intellectual vices which tend to lead to those fallacies, and the intellectual virtues that one can develop in order to reduce one’s tendency to make these mistakes.

Aristotle’s theory of intellectual virtue says that one of the most important functions of human beings is to reason. A good thing is one which fulfills its function well, and so it is good for humans to reason as well as possible: to reason excellently, to flourish in our expression of our capacity to reason. Certain characteristics or traits tend to promote an intellect which reasons excellently, and these are called virtues. Virtues are general habits or character traits, not strict rules. Learning them requires training and practice. Intellectual virtues are similar in this way to the “muscle memory” which allows you to tie your shoes, type on a keyboard, drive a car, or play a sport.

Virtues aren’t strict rules, but it’s helpful to think of them as the “middle ground” between two extremes of bad reasoning, or vices. A friendly person, for example, is neither totally disinterested nor obsessively interested in other people, but has a moderate degree of interest in others. A brave person is neither cowardly nor inclined towards stupid risks, but someone who falls in between those extremes. We recognize that a healthy diet requires moderation, neither eating too much nor eating too little, and a healthy blood pressure falls between “too high” nor “too low”. Similarly, by pointing out examples of the vices on either extreme, we help locate the intellectual virtues which avoid both extremes.

Fallacies

We’ve already discussed two fallacies in this course. Fallacies are specific expressions of intellectual vices which people are especially inclined to fall into. The first is the fallacy of non-sequitur, which happens when a conclusion is too distant from the premises, so that the conclusion doesn’t follow. The second is the fallacy of begging the question, which happens when the conclusion is too close to the premises, so that believing the premises requires someone to already believe the conclusion which is supposed to follow from them. Begging the question is a type of circular reasoning: the reason to believe A is B, but the only reason to believe B is A. This often happens when there is insufficient reason to believe the premises when they are considered independently from the conclusion.

In some sense, all of the mistakes in reasoning we will discuss involve one kind of error or the other. Either the truth of the conclusion doesn’t follow from the truth of the premises, making the argument invalid, or else there is insufficient reason to believe one or more of the premises is true when it is considered independently from the conclusion, meaning the reasoning is likely unsound.

Our tendency when we evaluate arguments is often to look at the conclusion first, rather than the reasons the conclusion is based on. If someone agrees with the conclusion, they ignore the reasoning and assume the argument is a good one. Often, however, bad reasoning can produce a conclusion we agree with, or a conclusion which is true. When seeking to develop the intellectual virtues and avoid fallacies, it is important to consider the reasoning behind a conclusion, not just whether the conclusion seems correct or incorrect.

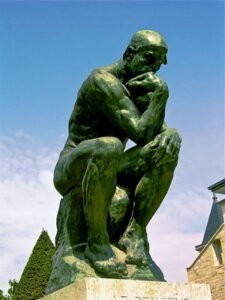

2.1.2 Proper Intellectual Self-Regard

Auguste Rodin, “Le Penseur”, 1881-1882, Sculpture (bronze), MusĂ©e Rodin, Paris, France

Intellectual Self-Regard

Becoming a more critical thinker begins with having an appropriate level of regard for oneself as a thinker. Whether you think of yourself that way or not, you are a thinker! If you’re currently reading and understanding this text, then you are currently thinking. In fact, if you consider all of the things which you might say about yourself, the one thing which is consistently true about all of your waking moments is that you are thinking. Whatever you might be thinking about at the time, you are never not thinking.

There are many doubts you may have about your abilities: you can have doubts about your ability to run a marathon, or pass a test, or do a job. One thing which you can’t doubt is your ability to think. Just try it! In the process of trying to doubt your ability to think, you will have to exercise your ability to think! You can imagine a lot of things about yourself changing; maybe you can imagine what it would be like to have eight arms and twelve eyes. You cannot imagine what it would be like to not be thinking.

So, since you are a thinking thing, as the philosopher Rene Descartes would say, it would benefit you to improve your thinking and to think as best as you can.

Insufficient Self-Regard

Many people learn as they grow up to disregard their own thinking ability. They learn, perhaps through social pressure, that they are not meant to be “thinkers”, but instead that they should leave the task of thinking to someone else. They believe that they aren’t “smart” or “logical” or “intellectual” enough, to think well. This becomes a problem, because it leads them to become unwilling to take ownership of their own level of knowledge or ignorance.

If this describes you, then in order to practice the principles of sound reasoning, you need to be begin by recognizing that you are ultimately the only one who could ever be responsible for your own reasoning. You are the only one responsible for whether you reason well or not: even if you were to try to outsource it to someone else, you’d still be responsible for the choice to outsource it.

The intellect is an amazing thing! You have an immense capacity to grow as a reasoner, provided that you are willing to regard yourself as a serious thinker capable of serious thoughts.

A person who lacks sufficient regard for their own intellect will tend to fall into fallacies of ignorance. These fallacies involve either embracing one’s own ignorance or “handing over the keys” of one’s own judgment to somebody else.

Irrelevant Authority

The fallacy of irrelevant authority occurs when someone accepts a claim on the basis of the testimony of somebody who has some kind of recognized authority or expertise, but their expertise is irrelevant to the claim. For example:

- Dr. Charles, a respected dentist, claims that love is the secret to happiness.

- Dentists are experts.

- Experts are generally right.

C. Love is the secret to happiness.

- Dr. Berkeley, who has a Ph.D. in psychology, claims that dental sealants are a useless hoax imposed by the dental supplies industry.

- Psychologists are experts.

- Experts are generally right.

C. Dental sealants are a hoax.

Sometimes this fallacy is called the “appeal to authority”, but not all appeals to authority are fallacies. If we switched the places of Dr. Charles and Dr. Berkeley in the arguments above, then their authority would be relevant: dentists should know about dental sealants, and psychologists likely know something about what makes people happy. In a courtroom, we defer to the authority of the judge, because the judge is an expert on the law; we would not necessarily grant the judge the authority to serve as a D.J. at a party, unless the judge also demonstrated some expertise in music. Ultimately, a critical thinker has to evaluate for themselves whether someone else’s authority and expertise is relevant to the question at hand.

Appeal to Ridicule

The fallacy of appeal to ridicule occurs when someone rejects a claim, because they believe they would look ignorant or be laughed at if they were to accept the claim. For example:

- Only crazy people think that time travelers live among us.

- You aren’t crazy.

C. You don’t think that time travelers live among us.

- No knowledgeable person believes that dirt has feelings.

- You are knowledgeable.

C. You don’t believe that dirt has feelings.

Both of these fallacies involve circular reasoning. It would only be ignorant to fail to accept the claim if it were false, yet it is only believed to be false because it would seem ignorant to believe it. Someone believes a claim is true, or false, only because someone else believes the claim is true, or false. Notice that there might be other, good, non-circular reasons to believe that love is the secret to happiness, or that dirt does not have feelings, of course, but fear of ridicule isn’t one of them.

Willful Ignorance

The fallacy of willful ignorance occurs when someone chooses to avoid or ignore reasons to doubt a claim because they want to continue to rationally believe the claim. For example:

- If there are good reasons to doubt that this policy will be effective, then I can’t rationally believe that this policy will be effective.

- I want to rationally believe that this policy will be effective.

C. There are no good reasons to doubt that this policy will be effective.

- If I read this article, then I will learn that smoking is unhealthy.

- If I learn that smoking is unhealthy, then I won’t continue smoking.

- I wish to continue smoking.

C. I will not read this article.

Appeal to Stupidity

At an even greater extreme, the fallacy of appeal to stupidity occurs when someone accepts a claim because it seems irrational to accept it, or rejects a claim because it seems rational to accept it. For instance:

- It is rational not to borrow more than you can repay.

- Rationality is boring!

C. You should borrow as much as you can.

- Max will probably lose the fight.

- I love an underdog!

C. Max will win the fight.

The easiest way to avoid these fallacies is simply by developing a degree of respect for your own intellect. Don’t settle for remaining ignorant when you don’t have to. When you hear an expert make a claim, don’t simply defer to their opinion; instead, make a habit of weighing in your own mind whether or not their expertise is relevant to the claim. When you hear a claim ridiculed as silly or absurd, don’t laugh at it right away, but instead make a habit of thinking of whether or not there are reasons to regard it as something false and worth dismissing. Make a habit of seeking to give yourself information instead of avoiding it. Doing this can help you put a high enough value on your own mind that you’ll only accept a claim when it seems justified.

2.1.3 Intellectual Humility

Intellectual humility means having the attitude of a student eager to learn more.

Intellectual Humility

While it is important to take your own intellect seriously, sound reasoning also requires not thinking too highly of your own intellect either. Respecting the knowledge and expertise of others, recognizing how much you don’t know, and recognizing your own tendency to make mistakes in reasoning is an important intellectual virtue. We call this Intellectual Humility.

Intellectual Humility includes recognizing the limits of your knowledge and understanding. It includes developing an appreciation that sometimes you are going to think you know things that aren’t true, that sometimes you’re not as much of an expert as you’d like to imagine; you may lack some information others have. Inevitably, sometimes you are going to be wrong.

One way to develop Intellectual Humility is through learning more. There is some truth to the saying, “The more you know, the more you know what you don’t know.” The less one knows, the easier it is to overestimate how much of the whole picture you have grasped. Learning often means learning that one’s assumptions were wrong, and the experience of being wrong can help with having a more realistic view of one’s own knowledge in the future.

It is easy to spot when other people think they know more than they really know. Naturally, it’s much harder to spot this trait in ourselves. Here are a few examples of fallacies that we can develop by thinking too highly of ourselves.

Immodesty

Intellectual Immodesty occurs when someone believes that their own knowledge is far more extensive than it really is. People are inclined to overestimate how much of the evidence available they have been exposed to, or underestimate how much there is that they don’t understand. Some examples:

- I have eaten at an Italian restaurant several times.

C. I know a lot about the culture of Italy.

- I’ve known Sid for years, and he seems like a nice guy.

- A nice guy would not do the horrible things Sid is accused of.

C. Sid did not do the horrible things he is accused of.

Hubris

Intellectual Hubris is a specific form of immodesty, which occurs when someone who isn’t an expert trusts their own judgment about a specialized topic more than the experts in that specialty. Instead of the mistake of deferring too easily to “experts”, even when their expertise is not relevant, overconfidence leads this person to fail to defer to experts when they ought to. Many of us have, after a long evening of intense internet searching, diagnosed ourselves with a serious disease, only to be reassured when visiting a doctor that they only have a commonplace ailment. Even greater intellectual hubris would involve insisting that the doctor is still wrong, trusting one’s own knowledge gleaned from hours of online searches over the Doctor’s years of medical education and experience.

Here is another example:

- My history professor claims that ancient Greeks knew the earth was a sphere.

- I know that everyone believed the earth was flat until 1492.

C. My history professor is wrong.

Appeal to Flattery

Appeal to Flattery, also called the “Appeal to Vanity”, is the opposite of the Appeal to Ridicule. In this case, someone is pushed to accept a claim because they believe they will seem more intelligent or otherwise praiseworthy if they accept the claim. For example:

- Brilliant people believe that there are degrees of infinity.

- You are brilliant.

C. You should believe that there are degrees of infinity.

- You are a warm, kind-hearted person.

- Warm, kind-hearted people support letting stray dogs run around freely.

C. You should support letting stray dogs run around freely.

Avoiding these fallacies requires keeping an accurate, modest assessment of what one knows and what one doesn’t really know. Developing that intellectual humility requires a willingness to be wrong at times, and at other times to live with uncertainty.

2.1.4 Respect for the Truth

The truth might be bigger than the pieces you see.

The desire to be right and the desire to have been right are two desires, and the sooner we separate them the better off we are. The desire to be right is the thirst for truth. On all counts, both practical and theoretical, there is nothing but good to be said for it. The desire to have been right, on the other hand, is the pride that goeth before a fall. It stands in the way of our seeing we were wrong, and thus blocks the progress of our knowledge.

V. O. Quine & J. S. Ullian, The Web of Belief

Respecting the Truth

It is good to desire the truth, but it is also important to respect the truth. To respect the truth is to regard it as (generally) independent from what we believe about it. Much like respecting a person means granting them independence from us and maintaining appropriate boundaries, respecting the truth is recognizing the boundary between our own beliefs about what the truth is, and the truth in itself independent of what we believe about it. Disrespecting a person means trying to violate their autonomy: seeking to control or manipulate them, or make them more dependent upon us, or not “giving them space” to be themselves. Similarly, disrespecting the truth means attempting to control or manipulate what truth is, to make it dependent on our own will, rather than giving it space.

Granted, there are a few truths which are dependent on our beliefs. For instance, the proposition expressed by “I believe that the sky is blue” is a truth, but what makes it true is not the color of the sky, but what I believe the color of the sky to be. Similarly, the truth of “I believe that molten lava is edible” depends on whether or not I believe it, not on whether molten lava is edible. “Most people believe that the sun is a star” is a truth which depends on what people believe about it; it is unlike the truth that “the sun is a star”, which was true even when most people didn’t believe it. Someone who says, “I am a libertarian”, or “I am very patriotic”, plays a role in making that claim about their own identity true about themselves.

Most truths are not like this, however. In general, when I believe something, even something very controversial, what I believe is not that I believe it, but that it is true whether or not I believe it. For example, when somebody believes that we ought to adopt stricter gun controls, what they believe is a claim about the world, that stricter gun controls would be good, rather than a claim about themselves and who they are.

Insufficient respect for the truth leads us to become more interested in justifying our existing beliefs than we are in knowing that our existing beliefs are justified. Most of us have this tendency, if we’re honest with ourselves, and it takes work to combat it.

Wishful Thinking

The fallacy of Wishful Thinking occurs when someone argues that a claim is true because it would be desirable if it were true, rather than on the basis of evidence that it is true. It confuses a reason to desire something to be true with a reason to believe that it is in fact true, or a reason to think things should be a certain way with a reason to think that they will be that way.

- I would like it if the Diamondbacks won the World Series.

C. I should place my bets on The Diamondbacks winning the world series.

- I don’t want to wear a seatbelt.

- If I were to be in a car accident, then I would want to wear a seatbelt.

C. I won’t be in a car accident.

It is not always irrational to expect what you want. We rationally expect our family and friends to help us out, for example. Since your own motivation plays a strong role in determining whether you are successful or not, believing that you will achieve your goals can motivate you, and thus helps make it true that those goals will be achieved. No sensible entrepreneur would believe that the business they’re starting is likely to fail, even statistics suggest it is likely to fail, because that would just help ensure it would fail! Sometimes wishful thinking is essential, because sometimes the truth depends upon us. Avoiding the fallacy requires knowing the difference between when what happens does depend upon us, and when it doesn’t.

Ad Hoc Reasoning

The fallacy of Ad Hoc Reasoning occurs when someone invents or “discovers” new reasons because they would justify their existing beliefs, rather than forming beliefs on the basis of their reasons.

For example, during the campaign for Women’s suffrage, someone who strongly opposed giving women the right to vote, but who couldn’t offer any justification for their views, might resort to inventing or making up reasons, like “women are too easily persuaded by politicians” or “politics will spoil the purity of women’s minds”, claims they suddenly began accepting solely for the purpose of justifying denying women the right to vote.

An easy way to check if your reasoning is ad hoc is to ask yourself: do I only believe this because it would justify something else I really want to believe?

- If it wouldn’t cost much to make College free for everyone, then College should be free for everyone.

- College should be free for everyone.

C. It wouldn’t cost much to make College free for everyone.

- If Spain sank the USS Maine, then we should go to war with Spain.

- We should go to war with Spain.

C. Spain sank the USS Maine.

Confirmation Bias

Confirmation Bias bias occurs when we interpret evidence in such a way as to support our existing beliefs, even when the evidence might support other beliefs, or might be neutral on the issue. Confirmation bias will even cause us to only look for, or only “see”, evidence which supports our existing beliefs, and to overlook evidence that does not support these beliefs. Confirmation bias leads us into circular reasoning.

- I think that Earl is a nice person.

- Greta said that Earl was a jerk to her.

- Either I am wrong about Earl, or Greta is trying to smear Earl’s reputation.

C. Greta is trying to smear Earl’s reputation

- There is some connection between cholesterol and heart attacks.

- Study A shows a connection between cholesterol and heart attacks.

- Study B shows no connection between cholesterol and heart attacks.

C. Study A is valuable evidence; and study B was hopelessly flawed.

Psychologists have shown that nearly all people suffer from confirmation bias to some extent, regardless of their degree of intelligence or education.

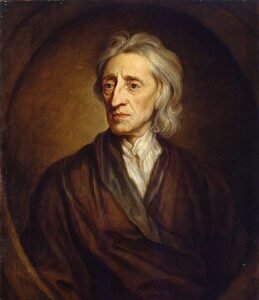

2.1.5 The Desire for True Beliefs

John Locke (1632-1704) was an English philosopher and political theorist.

He that would seriously set upon the search of truth ought in the first place to prepare his mind with a love of it. For he that loves it not will not take much pains to get it; nor be much concerned when he misses it…. I think there is one unerring mark of it, viz. The not entertaining any proposition with greater assurance than the proofs it is built upon will warrant.

John Locke, An Essay Concerning Human Understanding

Desiring the Truth

As Locke states, every inquiry begins with the love of truth, the desire to believe true things rather than false things. While it is important to respect the truth, as discussed earlier, our respect for the truth as something independent from us should not prevent us from trying to obtain knowledge about it. It is possible to respect truth so much that one gives up on it entirely, and concludes that the truth is so far beyond us that we can never hope to know it at all. The very word “truth” can start to sound so scary to someone that they don’t want to claim anything anymore.

It is possible to recognize our own tendency to make mistakes in reasoning, while still pushing forward and trying to reason as best as we can. We can both recognize that our opinions often get the facts wrong, and still try to hold opinions that get the facts right. The study of fallacies shouldn’t cause anyone to give up trying to form true opinions, since that itself would be a fallacy!

There are many ways in which people may “give up” trying to figure out what is true too soon. Two ways you have likely seen before we will call intellectual quietism, which gives up knowing the truth in order to avoid taking sides, and the who’s to say? fallacy, which gives up on knowing the truth in order to avoid feeling controlled.

Intellectual Quietism

Intellectual Quietism seeking to feel tranquil through taking a neutral stance over anything that can be debated. The Pyrrhonian Skeptics, for instance, were one group of “quietist” philosophers in ancient Greece who concluded that knowledge world were hopeless. Instead, they concluded the purpose of philosophy was to achieve tranquility through not forming a belief either way about anything that was potentially disputable. Since nearly everything can be disputed, they found, they suspended belief about nearly everything.

While it makes sense to neither believe nor disbelieve a claim when the evidence is equal on both sides, the fact that something is debatable does not mean the evidence is equal on both sides. People debate about many controversial issues, as well as issues that probably shouldn’t be controversial, but this doesn’t mean that the evidence is equally divided 50-50 for each side. The following are clearly fallacies:

- People on the internet debate about whether or not Bigfoot is real.

C. Therefore, I simply can’t know whether or not Bigfoot is real.

- People on the internet debate about whether or not Socrates really existed.

C. Therefore, I simply can’t know whether or not Socrates existed.

Who’s To Say?

The phrase “Who’s to Say?” is sometimes used to challenge a claim, by suggesting that the claim being challenged rests on the power or authority of the person making it, rather than on evidence. Using the phrase becomes a fallacy when it is used to challenge a claim that really does rest on evidence, when power and authority are irrelevant. For instance, suppose that Lars and Matt are having a debate:

Lars: I don’t want to eat this entire cheesecake, it has too much saturated fat.

Matt: Who’s to say it has too much fat?

Lars: The ingredients say it is made from cream cheese, which has a lot of fat, and a lot of fat isn’t good for me.

Matt: Who’s to say a lot of fat isn’t good for you?

Lars: My doctor advised me that I shouldn’t have a whole lot of fat in my diet.

Matt: Who does your fancy-pants doctor think he is anyway, the diet pope?

Lars: This advice was based on studies of heart disease over the last 50 years.

Matt: Sure, those are his facts, but who’s to say those have to be your facts?

Lars: Whoa, good point. Thanks for freeing my mind, Matt. This is delicious.

Although this is meant to be a silly example, Matt’s tactic here is similar to a tactic that you’ve probably heard people use in real life. When presented with evidence, instead of challenging the evidence, they challenge the authority or power of the person offering the evidence. They see the claim that something is true as an imposition of authority or power, so rejecting the claim is a way of avoiding being controlled by someone else.

2.1.6 Knowing What You Know

It’s important to recognize what you do know.

Knowledge and Skepticism

Sometimes a person is only right because they made a lucky guess. All of us have probably had the experience of guessing on a test and then finding out we were right. While we might celebrate the lucky guess, there’s nothing praiseworthy about guessing correctly. What’s valuable is actually knowing the truth, not just lucky guessing. Knowing the answer means not just getting the answer right, but getting it right because it is right, choosing it on the basis of some reason to think it is true. Knowledge is sometimes said to require justification for one’s beliefs, or to require that the beliefs be formed in a reliable way. This makes it more valuable than a lucky guess.

Because knowledge is valuable, once someone has it, they shouldn’t give it up too easily. For anything you think you know, it is very easy to come up with some way in which you might actually be wrong, to raise some doubt, or to lead you to not be quite sure anymore. For instance, do you really know that you are reading a textbook right now for a logic class, and not dreaming up the textbook and the class? How would you tell if you were? In spite of this hint of doubt, you still say that you know that you are reading your logic textbook.

Raising doubts in order to undermine knowledge is called skepticism. Some skepticism is very healthy, and intellectual humility requires a degree of skepticism even towards one’s own beliefs. At the same time, when taken to extremes, skepticism becomes a vice, because it undermines all of our knowledge. For example, an excessively skeptical person might always be doubting their own perceptions and memory of events, or irrationally suspicious that other people are lying to them, or insisting that we can never really know whether a claim is true or false.

Appeals to Ignorance

The appeal to ignorance argues we have reason to think a claim is true because we don’t “really” know it to be false: “for all we know”, the claim might be true. We can’t be entirely certain that ice cream doesn’t help cure athlete’s foot, for instance, since there have been no serious studies on the question, but this is not a good enough reason to dip one’s itchy toes into a chocolate sundae. A more subtle kind of appeal to ignorance argues that something is likely because we don’t know the answer to a question, any possible answer to the question is plausible. For example:

- We don’t really know that the majority of humankind doesn’t already live on another planet.

C. The majority of humankind really might live on another planet.

- We don’t really know what killed off the dinosaurs.

- An intergalactic thermonuclear war, or a mass suicide, would have killed off the dinosaurs.

C. An intergalactic thermonuclear war, or a mass suicide, really might have killed off the dinosaurs.

Appeal to Unpopularity

A stronger version of the appeal to ignorance is the appeal to unpopularity. It is hard not to be inspired by a good intellectual “David and Goliath” story, such as the story of Galileo Galilei’s trial by the inquisition for supporting Copernicus’s view that the earth resolved around the sun, not the sun around the earth. Unpopular opinions, like Galileo’s, which have been widely rejected by academic authorities of the day and ridiculed as absurd, declared heretical, or even made illegal, sometimes turn out to be true. These stories are inspiring because they are uncommon, though. The unpopularity of a view is not in itself evidence for its truth; what motivates someone to accept a view, simply because it is unpopular, is often just a desire to feel special or uniquely “in the know”. New, edgy, and controversial views are sometimes right, but often they’re not, and so simply being controversial or edgy is not evidence for the view.

- Everybody thinks they know that eating lead is bad for you.

- What everybody thinks they know is often wrong.

C. Eating lead is actually the solution to most of our health problems.

Conspiracy Theory

The most extreme result of excessive skepticism is conspiratorial thinking. Conspiracy theories weave together a series of appeals to ignorance and appeals to unpopularity into a web of ideas which gradually become more convincing as more is added to the web. Most people recognize that governments or organizations do sometimes lie about events or try to cover them up, and that some events are strange or hard to believe. For a conspiracy theorist, however, lies and cover-ups can become the default or normal explanation for any event which seems even slightly surprising.

- We can never really know when the government has a secret program.

- We can’t really know that there isn’t a secret government program to brainwash people into becoming mass shooters.

- There really might be a secret government program to brainwash people into becoming mass shooters.

- We don’t really know why there are so many mass shootings lately.

- If there were a secret government program to brainwash people into becoming mass shooters, that would explain why there are so many mass shootings lately.

C. Mass shooters are actually products of a secret government brainwashing program.

Conspiracy theorists know that their views are unpopular, but this is part of the appeal: believing the theory allows one to feel like they are “in the know”. Their arguments, however, rely on a series of appeals to ignorance. Unlike real cases in which a massive conspiracy is uncovered, there are no brave whistleblowers speaking out, no evidence of a conspiracy leaked out on the internet, no plausible motive, and many agencies independently investigating the crimes and looking for clues. Conspiracy theories only get a foothold when we ignore how much we do know.

2.1.7 Knowing What You Don’t Know

It’s important to recognize what you don’t know.

As we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns – the ones we don’t know we don’t know.

Donald Rumsfeld, U. S. Secretary of Defense (2002)

Knowing One’s Ignorance

While it is important not to give up possession of what we know, it is also important to be aware of how much we don’t know. The opposite of skepticism is credulity, believing that any information we have qualifies as knowledge. Credulity can result from trusting a vague perception or a fuzzy memory, or especially trusting rumors, hearsay, or other information from unreliable sources. Someone can even be too credulous when dealing with information that is fairly reliable but still uncertain, It is possible to believe something to be true, or to be probable, without believing oneself to know what one believes to be the case. For instance, rumors might be enough for me to believe that a certain coworker might be about to quit, and to start to prepare for the increased workload I’ll have when she leaves, without thinking that I know she is quitting and prematurely, and embarrassingly, buying her a good-bye card for everyone in the office to sign. Developing the ability to recognize when our own beliefs are tentative or speculative, and when they are knowledge, is an intellectual virtue.

Unwarranted Certainty

Recall that appeal to ignorance is the fallacy of concluding that because we don’t know something isn’t true, we have a reason to think that it is true. The reverse of an appeal to ignorance is unwarranted certainty, concluding that because we have some reason to think something is true, we know that it is true. Phrases like “we all know that”, “everybody knows”, or “they say” often hide unwarranted certainty: “they say that stuff causes cancer”, or “everybody knows that you can’t go there”. The move from probable to certain often happens in the middle of another argument, for instance:

- If Mike is not at work, then Mike is probably sick.

- Mike is not at work.

- Mike is probably sick.

- If Mike is sick, then Mike probably has the cold that is going around.

- Mike probably has the cold that is going around.

- If Mike has the cold that is going around, then Mike will probably be better tomorrow.

- Mike will probably be better tomorrow.

- If Mike will be better tomorrow, then we know it is safe to assign this project to him.

C. We know it is safe to assign this project to Mike.

Notice how in the middle of the argument, the word “probably” is quietly being dropped out. All that we really know for certain from the premises of the argument is that Mike is not at work, but by blurring the line between what we know and what is merely likely, we conclude that we know something which is not itself even probable.

Appeal to Popularity

Earlier we discussed the fallacy of the appeal to unpopularity, but what we encounter far more commonly is the appeal to popularity: the argument that because many people believe something to be true, it is true. Of course, appeals to popularity are persuasive precisely because the majority is usually right, at least when it comes to things that the majority of people experience. Taking a consumer survey is a good way to determine what brand of orange juice tastes the best, which brand of clothing feels the most comfortable, or which dish detergent or deodorant is most effective. Following the crowd is the smart option when you are trying to stay within your lane on on a highway during a thick dust storm, or escape through an open exit door in the thick smoke of a fire. Asking your classmates is a good strategy for figuring out what you missed in class.

Where the majority tends to be wrong is on issues more removed from what the majority of people experience, where only a few experts have knowledge. In those cases, the majority can be easily swayed by the voices which shout the loudest, have the most effective social media strategy, or have the largest advertising budget. In these cases, appeals to popularity are a kind of appeal to irrelevant authority. For example:

- Most Americans agree that increasing tariffs will not slow down the economy.

C. Increasing tariffs will not slow down the economy.

- Most of my single friends agree that this app is the best way to find a good relationship.

C. This app is the best way to find a good relationship.

Here we’ve polled the wrong group! If instead we’d polled most economists, or most people in good relationships, we might have more reason to think the majority opinion was a reason to believe the claim.

Mob Mentality

The most extreme consequence of a lack of adequate skepticism occurs in the mob mentality or groupthink, when information is quickly passed around from person to person with no tracking of the source of the information. Traditionally the mob mentality was associated with the behavior of large crowds of people, such as in riots: everyone within the crowd would feel compelled to follow the lead of those around them, and the crowd collectively would engage in behaviors (usually destructive) which no individual in the crowd consciously want to do. Most recently, the mob mentality is associated with forms of social media which allow many people to quickly spread a simple message, usually one carrying strong emotion (such as outrage or pity or shame) towards a particular target, with no time for analysis or verification, or consideration of proportionality.

- Everyone says that what @jerkface549 said was shameful.

- Whatever @jerkface549 said, I don’t know, but it was shameful.

- Everyone agrees that, if @jerkface549 said something shameful, the life of @jerkface549 should be ruined.

C. Whoever @jerkface549 is, I don’t know, but their life should be ruined.

While a conspiracy theory preys on a desire to have special and unique access to the truth for a person who feels rejected, the mob mentality preys on a desire to be like others and to belong to something greater. Both extreme skepticism and extreme credulity depart from the virtue of desiring knowledge.

Submodule 2.1 Quiz

Key Sources:

- Watson, Jeffrey (2019). Introduction to Logic. Licensed under: (CC BY-SA).

Next Page: 2.2 Managing Subjectivity