1.4 Rational Opinions

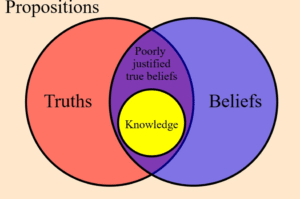

A belief or opinion is an attitude towards a proposition. It must be either true or false, even if we donŌĆÖt know whether it is true or whether it is false. Whether an opinion is true or false is different from whether it is justified or unjustified by oneŌĆÖs evidence or reasons.

One can hold a true opinion for good reason, or for bad reasons; one can hold a false opinion for good reasons, or for bad reasons. One should aim to hold justified beliefs, and this means avoiding forming beliefs through fallacious inferences.

1.4.1 Opinions and Beliefs

A Venn/Euler diagram which grants that truth and well-justified belief may be distinguished, and that their intersection is knowledge.

Opinions and Beliefs

A belief is an attitude towards a proposition. To believe a proposition is to hold that the proposition is true. Because the facts are what make propositions true, all beliefs are beliefs about what the facts are.

Some beliefs I am very certain of, like my belief that triangles have three sides, or my belief that I have two ears. I would be willing to claim that I know these things, in addition to believing them. Other beliefs I am not very certain of, like my belief that the Revolutionary War could have been avoided if cooler heads prevailed, or my belief that technology is making life better for humans. I would not claim that I know these things, only that I currently believe them. Whether I am certain or uncertain in a belief, the belief still makes a claim about the facts.

The word ŌĆ£opinionŌĆØ when it is used in philosophy typically means the same thing as ŌĆ£beliefŌĆØ. When I say, ŌĆ£In my opinion, technology is making human life better,ŌĆØ I am asserting that I believe that the proposition technology is making human life better is true. That proposition would be true if, among the facts in our world, it is a fact that technology is making human life better. So, opinions are about what the facts are.

Sometimes when people use the word ŌĆ£opinionŌĆØ or ŌĆ£beliefŌĆØ, they mean ŌĆ£mere opinionŌĆØ or ŌĆ£mere beliefŌĆØ, emphasizing that something is uncertain, or not knowledge. Later in our class, we will distinguish the degree of confidence or certainty someone has in a belief from the belief itself. We will study how evidence impacts the degree of confidence one should have towards a belief.

Every Opinion is Either True or False

Every opinion is a belief, and every belief is an attitude towards a proposition, holding that the proposition is true. Every proposition is either true or false depending upon what the facts are. So, every belief or opinion is either true or false, depending on what the facts are.

Some opinions are true. For example, my opinion that the sun is a star is true. Some opinions are false. For example, the opinion of some of the sailors aboard ColumbusŌĆÖs ships that they were going to fall off the edge of the world while sailing the Atlantic ocean was false.

Sometimes people use the word ŌĆ£opinionŌĆØ to emphasize opinions that are about things which are very hard to know, which nobody knows, or which only an individual knows for themselves. These are opinions, but they are still either true or false, depending upon whether they correspond to the facts. For example, somebody might hold the opinion that raising taxes would reduce economic growth, while another person might hold the opinion that raising taxes would not reduce economic growth. One of these opinions is true, and one is false, but it is very hard to know which is true and which is false. Somebody might hold the opinion that humanity will be extinct in 300 years. Either it is a fact that humanity will be extinct in 300 years, or it is not a fact, and so the opinion is either true or false. It is very hard, however, to know whether it is true or false. Alternatively, somebody might hold the opinion that, for them, cranberry juice is tasty. They alone know whether or not cranberry juice is tasty for them. You and I canŌĆÖt experience what cranberry juice tastes like for them. We can only experience it for ourselves. Still, their opinion that ŌĆ£cranberry juice is tastyŌĆØ is either true or false, depending upon whether in fact they authentically experience it as tasty or not.

1.4.2 Justifying Beliefs

A belief is justified when it is supported by sufficiently good reasons.

Justifying Beliefs

Beliefs can be held for good or bad reasons. A good reason to believe that you have won a sweepstakes is receiving a check from a sweepstakes, depositing it, and having the funds successfully clear a bank account. A bad reason to believe that you have won a sweepstakes is receiving a pre-recorded message on your cell phone that does not address you by name, claiming that you are a winner and asking for your bank account information.

The reasons someone holds a belief do not determine whether the belief is true or false. Someone can hold a true belief for bad reasons. For example, suppose that you hear a rumor that somebody in at your workplace is planning to quit, and you really hope that your boss will be the one to quit. This isnŌĆÖt a good reason to believe that your boss will quit, but your belief, though unjustified, might still be true.

Someone can also hold a false belief for good reasons. For example, a jury might hear testimony that establishes the defendant had the motive, means, and opportunity to commit the crime, DNA establishes that they were present on the scene, and the police have recorded a confession. The jury would have good reasons to believe the defendant is guilty. Still, it might have been a coerced confession, the DNA might have been planted, and the defendant might have had nothing to do with the crime. The jurorsŌĆÖ beliefs were justified, but false.

Reasons or evidence, or a lack of reasons or evidence, are not what make a belief true or false. The way reality is makes a belief true or false. Instead, reasons or evidence are what make a belief more certain or less certain, justified or unjustified, or make it the case that you should be more confident or less confident about it.

Inferences and Justification

An inference is a transition from a reason to a conclusion formed on the basis of that reason. Here are some examples of inferences.

Reasons: Everyone in my floor of the dormitory has signed up for the fiesta, and Jenn is on my floor.

Conclusion: Jenn has signed up for the fiesta.

Reasons: WeŌĆÖre either going to Panama or Cuba for vacation, and weŌĆÖre not able to go to Cuba.

Conclusion: WeŌĆÖre going to Panama for vacation.

Reasons: My neighbor constantly blares music between 10pm and 1am every night.

Conclusion: My neighbor will constantly blare music between 10pm and 1am tonight.

We want all of the inferences in an argument to be good inferences. This means we need to avoid inferences which are (a) redundant or uninformative, or (b) wild leaps beyond what the reasons are reasons for.

A belief is typically justified when there are sufficiently good reasons to believe it and no sufficiently good reasons to doubt it. This often means that the belief has been inferred as a conclusion from good reasons.

Rationality means aiming to believe all which one is justified in believing, but only what one is justified in believing, to the extent possible. It is difficult to define a precise point when a belief has sufficiently good reasons to believe it, or sufficiently good reasons to doubt it. So, there is no perfect test for justification or for rationality. Nonetheless, we can often recognize when an inference would be rational or irrational. An irrational inference goes far beyond what the reasons justify us in concluding. A rational inference sticks within the limits of what the reasons justify us in concluding.

Justification and rationality are not the same thing as truth. What makes something true or false are the facts in the real world, independent of what we know about them. But what makes something justified or unjustified, rational or irrational to believe, is our evidence. Typically, our evidence matches up with the facts in the real world! So, typically justified beliefs are true beliefs, and typically false beliefs are not justified beliefs. Sometimes, it is irrational or unjustified to hold a belief which is true. Sometimes, it is rational or justified to hold a belief which is false. One trusts that this isnŌĆÖt generally the case, however, and so forming justified beliefs is the best strategy to generally believe what is true.

1.4.3 Non-Sequitur Fallacies

A “non-sequitur” is an inference which isn’t valid.

The Fallacy of Non-Sequitur

The Latin phrase non-sequitur means ŌĆ£it doesnŌĆÖt followŌĆØ, and we say that an inference commits the fallacy of non-sequitur whenever the conclusion doesnŌĆÖt follow from the premises. When we say that the conclusion ŌĆ£doesnŌĆÖt followŌĆØ, we mean that the conclusion goes farther than the reasons justify. It concludes too much.

For example, this inference is a non-sequitur:

Reason: Clowns are amusing to most children.

Conclusion: Jimmy would like a clown for his birthday party.

The conclusion doesnŌĆÖt follow, because reasons donŌĆÖt tell us that Jimmy likes clowns; and even if Jimmy does like clowns, that might not be what he wants at his birthday party.

This inference is also a non-sequitur:

Reason: Clowns are good at attracting attention, and politicians need to attract attention.

Conclusion: Clowns should run for political office.

The conclusion doesnŌĆÖt follow, because there are a lot of other important factors involved in political office besides attracting a lot of attention.

Some non-sequiturs are more subtle, however:

Reason: Over 95% of clowns who took a daily dose of banana cream pies did not die of a heart attack within a 2 year period.

Conclusion: Banana cream pies prevent heart attacks.

At first, it might be tempting to draw the conclusion that there is some connection between eating banana cream pies and avoiding heart attacks. When we think about it more, however, we can see that the conclusion doesnŌĆÖt follow. There is probably a much better explanation for the statistic. For instance, it is true that 99.8% of Americans in general donŌĆÖt die of heart attacks within a given 2 year period, whether they eat banana cream pies or not.

Here is another subtle non-sequitur:

Reason: Wholesome Groats Cereal is Fortified with 20 essential vitamins and minerals which are part of a healthy diet.

Conclusion: Wholesome Groats Cereal is part of a healthy diet.

Why doesnŌĆÖt the conclusion follow? Well, keep in mind that we havenŌĆÖt been told what else Wholesome Groats Cereal contains, in addition to those essential vitamins and minerals. We havenŌĆÖt, for example, been told whether or not it contains radioactive material, lead shavings, or high levels of artery-clogging fats. It might be a very unhealthy food to eat.

Non-sequiturs can be very difficult to catch. How do we avoid making ŌĆ£skipsŌĆØ or ŌĆ£jumpsŌĆØ in our reasoning? As we discussed earlier, in logic, we use the notion of validity. A inference is valid whenever there is no possibility of the conclusion being false when the reasons we used to infer the conclusion are true. In other words, when an inference is valid, we know the conclusion is true if we know the reasons for the conclusion are true. This is a very strict standard, and much stricter than the standard most people use everyday. Many inferences that most people would say ŌĆ£followŌĆØ by everyday standards are still not valid by the standards of logic. Logic insists on this high standard because we recognize that non-sequiturs are often hard to catch.

1.4.4 Begging the Question

Circular reasoning leads right back to where it started.

Begging the Question

The opposite of the Fallacy of Non-Sequitur is the fallacy of begging the question. While in a non-sequitur the reasons the conclusion are too far apart, an inference which begs the question is one in which the reasons and the conclusion are much too close, so close that no one would accept the reasons if they didnŌĆÖt already accept the conclusion!

Begging the question is also known as circular reasoning, because the ŌĆ£reasonsŌĆØ in the argument are only probable when someone already accepts the conclusion. For example:

Reasons: Toasters are deadly.

Conclusion: Toasters can kill you.

The inference is valid, because if toasters are deadly, then toasters can kill you. The argument is question-begging, however, because someone who wants to know why you believe toasters can kill you is not going to accept as an answer, ŌĆ£because they are deadly.ŌĆØ ThatŌĆÖs simply repeating the conclusion in other words.

Another example:

Reasons: Children should not have smartphones.

Conclusion: Smart phones are a danger to children.

It may be true that children should not have smartphones, and it may be true that smart phones are a danger to children. This inference is backwards, however: the ŌĆśconclusionŌĆÖ is actually the reason, and the ŌĆśreasonŌĆÖ is the conclusion. Believing that children should not have smartphones is not the reason someone concludes that they are a danger. Instead, if smart phones are a danger to children, such as the increased risk posed by cyberbullying to children who have them, then that is a reason to believe that children should not have smart phones.

Here is a more complicated example:

Reasons: NASA told the public that there was a moon landing, but the moon landing was a fake and they knew it.

Conclusion: NASA lies to the public.

This inference is valid, because the conclusion does follow from the reasons. If itŌĆÖs true that the moon landing was a fake, and NASA knew that but still claimed it was real, then it must be true that NASA lies to the public. Notice, though, that the conclusion is more likely than the reasons given for it. It is more likely that NASA lies to the public than it is that the moon landing was a fake. Someone must already believe that NASA lies to the public if they are willing to conclude that NASA faked the moon landing; someone who believes that NASA never lies to the public isnŌĆÖt going to be persuaded by someone saying, ŌĆ£What about the moon landing?ŌĆØ

The more deeply embedded a belief is within our system of beliefs, the easier it is to not realize that we are begging the question when we draw that belief as a conclusion. For example, both of the following are examples of begging the question:

Reason: Some events are miracles

Conclusion: God exists

Reason: No events are miracles

Conclusion: God does not exist

Whether someone interprets events as involving divine intervention or not will depend on whether or not they already believe or disbelieve in a divine being. If someone believes in an all-powerful God, then nearly all events are going to involve divine influence to some degree. If someone does not believe in divine or supernatural beings of any sort, then no event, however improbable, could count as miraculous. So, in both of the inferences above, someone already had to accept the conclusion in order to accept the reason given for the conclusion, making the reasoning circular.

Submodule 1.4 Quiz

Licenses and Attributions

Key Sources:

- Watson, Jeffrey (2019).┬ĀIntroduction to Logic. Licensed under: (CC BY-SA).

Next Page: 2.1 Proper Regard