2.2 Managing Subjectivity

Our own subjectivity is an inescapable and essential to who we are. It would be a mistake to ignore the role that our individual perspective plays in shaping our judgments, and it would be a mistake to try to write off all emotions as unreasonable.

At the same time, we can seek to reason more objectively than we tend to by default, by taking a step back from our particular circumstances, feelings, and interests, and trying to think of them from the outside. Learning how to manage oneŌĆÖs own subjectivity is an important part of becoming a better reasoner.

2.2.1 Self-Awareness

Shark attacks are rare but memorable, so people overestimate their frequency.

The Virtue of Self-Awareness

In the context of reasoning, self-awareness means being aware of the standpoint from which one views the world. Each of us comes from a particular background, which will inform us of some small sliver of human experience; we each have different kinds of experiences and expertise, which make us more informed than others about some things and less informed about others; each of us pays close attention to some features of the world which others ignore, and ignores some features which others pay close attention to. A good reasoner, who has developed the intellectual humility discussed previously, knows when something falls within or outside of their own experience, and does not pretend to be more informed than they are. The opposite of self-awareness is the vice of pretentiousness, pretending to know what one does not.

Presumptuous Objectivity

ŌĆ£PresumptuousŌĆØ objectivity means thinking that oneŌĆÖs own perspective presents a fully accurate, all-encompassing, and objective view of the world, and that it is always other people who suffer from an excessively narrow point of view. Naturally, I am the one who has seen and weighed all of the evidence in an even-handed and unbiased way; other people are the ones who are biased. Since no one living is entirely free from the impact of biases or able to know all of the information others have, anyone who views themselves as free of biases is clearly biased towards themselves, and lacking in self-awareness. For example:

- It seems to me that a universal basic income would easily solve poverty.

- It seems to John that a universal basic income would just lead people to stop working.

- John works a difficult job doing skilled labor, so his views are very narrow, and how things seem to him is inaccurate.

- I work at a university, so my views are universal, and how things seem to me is accurate.

C. A universal basic income would easily solve poverty.

Presumptuous Familiarity

Presumptuous familiarity occurs when a person claims that they have a more objective view of another person, and the inner workings of that personŌĆÖs intentions and motivations, than the other person has of themselves. This might involve claiming to know that even though somebody else thinks they want something, what they really want is something else.

With close friends or family members, this isnŌĆÖt always presumptuous; itŌĆÖs not presumptuous for the a parent of a small child to conclude that the child throwing a fit over a sock that is out of place is actually just tired and needs a nap, or for the adult child of a questioning parent to recognize that the parent who seems to be asking intrusive questions really is just lonely and just wants to talk. The fallacy occurs when somebody claims to know the mind of somebody who they donŌĆÖt know very well, like a politician who claims his opponents only disagree because they hate him personally, or when a driver infers that another car on the road is intentionally acting in an annoying way. WhatŌĆÖs often happening in these cases is often a case of projection: taking oneŌĆÖs own hidden intentions and motivations and imposing them onto the behavior of somebody else.

- I know Alan says he supports gun control in order to reduce violent crime.

- I know Alan feels weak and powerless.

C. I know Alan really supports gun control in order to vicariously control the lives of others and compensate for his own weakness.

- I know Dan says he opposes gun control in order to preserve individual freedom.

- I know Dan feels weak and powerless.

C. I know Dan really opposes gun control in order to maintain the fantasy of power he gets from having a large arsenal of guns.

Presumption and Memory: The Availability Heuristic

The availability heuristic is a very common way in which most of us lack self-awareness: we assume our memory objectively represents how commonplace an event is. When itŌĆÖs easy to remember an example of something, people judge it to be more typical or normal than when it is difficult to remember an example of something. We imagine that looking through our memories is like searching the pages of an encyclopedia, but it isnŌĆÖt objective in that way. Instead, events tend to be easier to remember when they are especially vivid, frightening, shocking, emotional, or connected with images or other sensations. For example:

- It is easy to remember stories about famous criminals who were from Italy.

- It is not easy to remember stories about famous stock-market investors who were from Italy.

C. People from Italy are more likely to be criminals than stock-market investors.

- I can easily remember vivid scenes of terrorist attacks.

- I canŌĆÖt easily remember vivid scenes of household accidents.

C. Reducing terrorism would save more lives than reducing household accidents.

The conclusion of each argument is false, but people regularly infer false exclusions exactly like these in similar cases. How easy or difficult it is to remember something is not a reliable measure of how common an occurrence it is. Recognizing that oneŌĆÖs memory will inevitably make it easier to remember shocking or emotional information than ŌĆ£boringŌĆØ information is an important part of self-awareness.

2.2.2 Objectivity

Try to weigh the evidence in your own mind.

Seeking Objectivity

Even while being aware of the limitations of our own perspective, we can still aim to reason in a more objective way than we currently do. Attempting to be more objective means trying to reduce the impact of our biases, cases where we consider a claim more likely to be true because of its relationship to ourselves, a group we identify with, or our cultural and social norms. All people have biases, and this isnŌĆÖt always a bad thing: what would we think of a parent who wasnŌĆÖt biased towards their own child, or of a friend who didnŌĆÖt favor their own friends? The trouble comes in when we mistake a feeling of closeness or loyalty to something for evidence.

Seeing objectivity means trying to temporarily detach ourselves from the particularities of our situation in life. The philosopher John Rawls called this the ŌĆ£Veil of IgnoranceŌĆØ: imagining that we donŌĆÖt yet know our own sex, race, nationality, relationships, social status, talents, or individual tastes, and trying to figure out what rules we would want to live under if we didnŌĆÖt yet know who we would be.

One useful way to categorize biases is by the source of the bias, and whether the bias comes from ourselves, from a group with which we identify, or from a general sense of what is normal around us.

Individual Bias

Individual bias is when we allow our closeness to our own situation to dominate our judgment, so that we fail to account for all of the information we donŌĆÖt have access to from our perspective. For example:

- I could really use a raise right now.

- I work very hard.

C. I really deserve a raise right now.

Although the premises may be true, the conclusion doesnŌĆÖt follow. IŌĆÖm not accounting for factors like the overall profitability of the company, the other people who might deserve raises before me, or so on. Another example:

- I see myself cleaning up all the time, and almost never see my roommates cleaning up.

C. I do more work cleaning up than my roommates.

This is a very common fallacy in roommate situations! Each roommate sees 100% of the work that they do, but only a small percentage of the work that the other roommate does, and so each roommate wrongly thinks that theyŌĆÖre doing the majority of the work.

Individual bias can also lead us to unrealistic beliefs about people who are close to us. For instance, a parent might reason:

- My child is amazing at math.

C. My child is the best at math in the entire school.

Although thereŌĆÖs nothing wrong with preferring oneŌĆÖs own child over others, biased beliefs can quickly infect our reasoning if we donŌĆÖt identify them. Again:

- My friend says that Jess said something insulting to her, and didnŌĆÖt tell me any reason why Jess said it.

C. Jess had no reason for what she said to my friend.

Ingroup Bias or Tribalism

Another kind of bias comes the various groups or ŌĆ£tribesŌĆØ which we affiliate with or identify with. Most people rely on membership in a community (or variety of communities) to help offer a support network and a sense of orientation to their lives, and every community must have, in order to persist as a community, boundaries which establish some ŌĆ£in groupŌĆØ who belong, and some ŌĆ£out groupŌĆØ who donŌĆÖt belong. This in itself isnŌĆÖt a problem, but when we allow this bias to infect our reasoning, this can lead to the fallacy of ŌĆ£TribalismŌĆØ, where we think that what benefits our community, or what our community says, is more likely to be right than what benefits another community, or what another community says.

Historically, community bonds tended to be shaped by geography, and so the easiest kinds of bias to spot are geographical:

- I am a fan of the Phoenix Suns.

C. The Suns will probably win the game.

- Our neighborhood is full of kind, hard-working people who are victimized by criminals.

C. Our neighborhood deserves a greater share of police resources than other neighborhoods.

- If solar energy is the solution to climate change, then Arizona will be rich.

- I am an Arizonan.

C. Solar energy is the solution to climate change.

Ethnic and religious identity often transcends geographical boundaries, but can also be a widely-recognized source of ingroup bias, as debates about topics like immigration can often bring to the surface. In particular, we can make the faulty inference that someone in the out-group is less trustworthy as a member of society in general simply because they donŌĆÖt participate in the mutual trust which binds the in-group together.

- We fellow Huguenots trust and rely upon one another intensely.

- Eric is not a fellow Huguenot.

C. Eric is not a trustworthy or reliable person.

The hardest to recognize source of ingroup bias, however, is probably affiliation with some political party or ideological group. This can be harder to recognize, because people affiliate with a group for good reasons, usually because the group agrees with views the person already holds on various issues. The problem arises when the reasoning is reversed, and people form views based on what will line them up with the group. For instance, it isnŌĆÖt bias if a person who has generally liberal or conservative political views tends to think that their liberal or conservative political group is generally right. Where we see the dangerous influence of ingroup bias is when the position of the group is what determines the views of its members, rather than the views of the members determining the position of the group. Were the political groupŌĆÖs leadership to suddenly adopt a drastically different view, the members of the group would change their views to remain in step. For example:

- On Tuesday, the party said we should allow prostitution.

- On Wednesday, the party said we should ban prostitution.

- I am a loyal party member.

C. We should allow prostitution on Tuesdays and ban it on Wednesdays.

Normality or Legality Bias

The last source of bias has to do with using what is normal around us as guidance for what is normative or morally right, when in fact what is normal around is a reflection of cultural or social norms that have no moral justification. Some social and cultural norms do have moral justification, of course: for instance, saying please or thank you are cultural ways of communicating moral respect for other people. There are other cases in which a cultural practice can be morally neutral (like the way in which a person crosses their legs), or morally negative (like a cultural practice of harassing women), however. The fallacy of normality bias confuses cultural norms with objective norms:

- People in our culture donŌĆÖt normally talk to their dogs.

- Jeff talks to his dog.

C. Jeff is insane.

The same is true of legal norms. Some laws are morally justified (like laws that prohibit murder), some laws are morally neutral (like driving on the right rather than the left side of the road), and some are morally negative (like the Jim Crow laws mandating segregation). It is a fallacy to confuse legal norms with moral principles; moral principles might be at the basis of a legal norm, but theyŌĆÖre not guaranteed to be:

- Gambling on sporting events is illegal in this state.

C. Gambling on sporting events is morally wrong in principle.

So, the fact that something seems normal or abnormal to us is not enough evidence in itself that that it is objectively right or wrong, until we consider carefully whether our sense of what is normal is being influenced by bias.

2.2.3 Emotion and Morality

Adam Smith (1723-1790) wrote on the importance of the moral sentiments.

Emotion and Morality

Most of us already recognize that strong emotions are a frequent cause of errors in reasoning. People make poor inferences because they are angry or exhausted, or because they are over-enthusiastic. Unfortunately, this can lead us to sharply contrast emotion and reason, or to create a false dichotomy between being emotional and being logical. This is misleading, because it suggests that someone becomes ŌĆ£logicalŌĆØ by removing all traces of emotion: something like the character Lieutenant Spock from Star Trek. Unlike Vulcans, however, humans who suppress their emotions also tend to suppress their sense of morality, by suppressing feelings of compassion, of fairness, and of the obligation to repay what we owe. A psychopath, for instance, typically lacks feelings of guilt and remorse.

Philosophers like David Hume and Adam Smith (whom you might recognize as the founder of modern Economics) emphasized the close link between morality and moral sentiments, like feeling bad after having hurt someone, or feeling good about having helped someone. Both Hume and Smith were certainly ŌĆ£logicalŌĆØ people, but they didnŌĆÖt think this meant they couldnŌĆÖt also be ŌĆ£emotionalŌĆØ people. Although strong emotions can lead to bad reasoning, it can also be reasonable to feel strong emotions when thinking about important moral issues.

There are two fallacies which people can fall into when they too closely oppose being ŌĆ£emotionalŌĆØ from being ŌĆ£logicalŌĆØ, both involving moral claims. We can call these fallacies of indifference, since they result from lacking emotional reactions that a reasonable person would have.

Amoralism

Amoralism is the fallacy of concluding that, because a moral claim is associated with strong emotions, and emotions are not ŌĆśrationalŌĆÖ or a guide to truth, the moral claim must be false. Although we shouldnŌĆÖt accept someoneŌĆÖs moral claim simply because they happen to feel strongly about it, we do know that morality tends to impact people emotionally, and so we shouldnŌĆÖt discount a moral claim simply because someone feels strongly about it. For instance, both of the following are fallacies:

- People who say murder is wrong are motivated by strong emotions.

- Strong emotions are no guide to truth.

C. Murder isnŌĆÖt wrong.

- The crime victim is extremely emotional.

- Being emotional is irrational.

C. The crime victim is extremely irrational.

Deriving an Ought from an Is

The fallacy of ŌĆ£deriving an ŌĆśoughtŌĆÖ from an ŌĆśisŌĆÖŌĆØ, identified by David Hume, is the fallacy of looking to some emotion-free ŌĆ£cold, hard factsŌĆØ, or impersonal statements about what ŌĆ£isŌĆØ, to inform us about morality, or how things ŌĆ£ought to beŌĆØ or ŌĆ£should beŌĆØ, or what is right or wrong, or good or bad.

- In nature, all species aim to survive and reproduce.

- Spaying or neutering cats prevents them from reproducing.

C. Spaying or neutering cats is wrong.

To see that this is an example of the Is-Ought fallacy, we can add a third premise. This third premise is necessary to make the argument valid: to make it so that the truth of the premises would guarantee the truth of the conclusion. Without this premise, the argument wouldnŌĆÖt be valid. Adding the third premise, however, will reveal that weŌĆÖre deriving an ŌĆśoughtŌĆÖ from an ŌĆśisŌĆÖ:

- In nature, all species aim to survive and reproduce.

- Spaying or neutering cats prevents them from reproducing.

- If nature aims at something, then we ought to never prevent it.

C. Spaying or neutering cats is wrong.

Not every moral claim is a fallacy. Many ethicists accept that sometimes facts about how things are can justify moral Oughts. As John Searle argued, the fact that I made a promise is reason to think that I ought, all other things being equal, to keep that promise; as Jeremy Bentham held, the fact that something produces more pain than some otherwise equal but less painful alternative is a reason to think that choosing the more painful option is wrong. It is when we pretend that we are removing any kind of personal, human, or emotional consideration from the picture that we fall into the Is-Ought fallacy.

2.2.4 Emotion within Reason

Stoics like Marcus Aurelius (121-180) sought to guide emotion by reason.

The Virtue of Intellectual Temperance

A reasonable person can have strong emotions; the key is to ensure that their emotions are being guided by their reasoning, rather than their reason being guided by their emotions. For instance, someone should feel angry because an injustice was done, rather than concluding than an injustice was done only because they feel angry. Similarly, someone should feel sad when they rightly perceive something bad to have happened, or feel happy because they rightly perceive something good to have happened. This is sometimes called the appropriate ŌĆ£direction of fitŌĆØ: our emotions aim to fit reality, reality does not aim to fit our emotions. Intellectual temperance is the virtue of having emotions that respond to reasons in reality. The opposite of intellectual temperance, forming unjustified beliefs on the basis of emotions, leads to the fallacies of emotional appeals.

Emotional Appeals

We have already discussed why wishful thinking is a fallacy, assuming that the truth will line up with what we desire. Emotional appeals are similar to wishful thinking, since they assume that the truth lines up with what emotions like pity or anger lead us to desire. We can categorize emotional appeals by the type of emotion to which they appeal.

Appeal to Pity, Desperation, or Despair

Appeals to pity, desperation, or despair rely on producing sad feelings in the reasoner, which leads the reasoner to conclude that something couldnŌĆÖt possibly be false, because it would simply be too sad if it were false.

- Either Greg has a month left on his lease, or Greg will be kicked out of his apartment.

- It would be so sad for Greg if he were kicked out of his apartment.

C. Greg has a month left on his lease.

Learning ways to cope with and accept sad emotions can help with interpreting the world more accurately and avoiding these fallacies.

Appeal to Anger or Spite

Appeals to anger or spite rely on producing a strong feeling of having been wronged or unjustly treated in a reasoner, so that the reasoner is willing to accept that something is true because it would make it easier to justify taking revenge.

- It would be an outrage if the enemy got away with crimes against humanity.

- If we sign the peace treaty, then the enemy will get away with crimes against humanity.

C. We shouldnŌĆÖt sign the peace treaty.

Appeal to Charm, Humor, or Glory

Unlike appeals to pity or anger, appeals to charm (how charming someone is), humor (how funny someone or something is), or glory (how amazing something would feel) rely on producing positive, upbeat, or amused feelings in a reasoner. These positive feelings are enjoyable, but they can make it easy to accept something as true which wouldnŌĆÖt be accepted if one was more critical.

- Charlotte is a hilarious comedian.

- Charlotte says that we should colonize the moon.

C. We should colonize the moon.

Appeal to Peace or Calm

Lastly, an appeal to peace or calm argues that a claim should be accepted (or rejected), not because of evidence for or against the claim, but because it would be troubling, disruptive, unharmonious, or would lead to conflict if it were not accepted (or rejected) as true.

- If you disagree with my claim, there will be bitter conflict between us.

- We should seek peace rather than conflict.

C. You should not disagree with my claim.

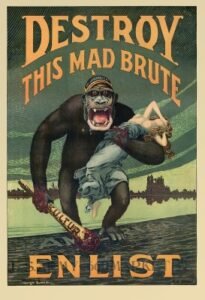

Emotive Language or Images

While all of the emotional appeals above have been laid out explicitly, as formal arguments, emotional appeals are not typically made explicit. Instead, writers or journalists will use emotionally-loaded language or other rhetorical strategies to appeal to emotion without making it look as though they are appealing to emotion, or they will accompany what they are saying with images that evoke strong emotions they want someone to have in mind when interpreting the story. One test for whether rhetoric is disguising an emotional appeal is whether the same emotions would remain if the information were presented from a different point of view, with differing language and imagery. If the information itself contains good reasons to feel pity or anger, then these feelings should remain stable; but if the emotions are evoked not by the information but by the language or images, then there might be a disguised emotional appeal.

2.2.5 Intellectual Courage

Propaganda often appeals to fear.

The Virtue of Intellectual Courage

Intellectual courage is the commitment to seek a knowledge of what is true even when the truth, or a belief in the truth, would have negative consequences. It is an extension of the virtues of the desire for knowledge, and the love of truth for truthŌĆÖs sake, which we discussed earlier.

Good reasoning is concerned with the logical consequences of a view. If something false is a logical consequence of a claim, then it is right to reject the claim itself is false. For instance, suppose someone claims that they are at least 21 years old, and a logical consequence of that is that their birthday was over 21 years ago, but I know that this personŌĆÖs year of birth was only 18 years ago. Good reasoning rejects the claim that they are at least 21 years old.

We are often persuaded by negative practical consequences, however, rather than logical consequences. We worry that accepting a claim is true would require something inconvenient, difficult, or scary — or that accepting it would lead other people to insult us or try to harm us. Out of fear, we refrain from believing the claim is true. What we need to develop is greater intellectual courage.

Appeal to Consequences

An appeal to consequences occurs when someone argues that if a claim were true, then something undesirable would follow, but because we would not want those undesirable consequences, the claim itself must be false. For example:

- If climate change were influenced by humans, I would feel guilty about my lifestyle of excessive consumption.

- I donŌĆÖt want to feel guilty about my lifestyle of excessive consumption.

C. Climate change is not influenced by humans.

- If the governor is guilty, then he must be impeached.

- We donŌĆÖt want to impeach the governor.

C. The governor is not guilty.

Appeal to Fear

An appeal to fear an appeal to consequences which also appeals to a specific emotion, fear. Like appeals to emotion, it relies on generating feelings of fear in a reasoner, and then leading the reasoner to conclude that because something is frightening, it must be false. For instance:

- If I believe that war is approaching, then I will fear losing my investments.

- I shouldnŌĆÖt fear losing my investments.

C. War is not approaching.

- It would be truly frightening if nuclear weapons were in the hands of an unstable person.

- Nuclear weapons are in the hands of the dictator of a small non-developed country.

C. The dictator of the small non-developed country is not an unstable person.

Appeal to Force

An appeal to force is both an appeal to consequences and an appeal to fear, where the person making the argument is themselves the source of the fear. An appeal to force is a fallacy, since it involves threatening someone to come to a conclusion rather than persuading them through reasons.

- If you donŌĆÖt agree with me, then I will have you arrested.

- You donŌĆÖt want me to have you arrested.

C. You should agree with me.

2.2.6 Intellectual Caution

Cautiously consider what a claim would entail down the road.

Intellectual Caution

Intellectual caution involves seeking to refrain from forming false beliefs. Intellectual caution includes a willingness to avoid ŌĆśtaking sidesŌĆÖ if neither position on an issue has sufficient evidence to justify belief. While intellectual courage frees us from having to consider negative practical consequences when determining what is true, intellectual caution requires that we consider the logical consequences of a belief. Often, a claim which is exciting or tempting to believe will turn out to have logical consequences that canŌĆÖt simultaneously be accepted as true. Intellectual caution encourages us to think of the (logical) consequences of a belief before adopting it.

The Fallacy of the Self-Undermining View

A view which either contradicts itself, or implies that one shouldnŌĆÖt believe the view, is what is called a self-undermining view. Self-undermining views can be defended with valid arguments, where each premises seems likely, but when thinking about the argument carefully, no one can believe the premises if they believe the conclusion. For example:

- If sentences in English have meaning, then there is an authoritative source which establishes the meanings of words.

- There is no authoritative source which establishes the meanings of words.

C. Sentences in English have no meaning.

This is a valid argument, but if someone accepts the conclusion, then the argument itself wouldnŌĆÖt mean anything, since the argument is composed of sentences in English. The argument is self-undermining. To give another example:

- No one should believe there is a fact of the matter about controversial claims.

- Claims about what one ŌĆśshouldŌĆÖ do are controversial.

C. No one should believe there is a fact of the matter about claims about what one ŌĆśshouldŌĆÖ do.

According to the conclusion, no one should believe the conclusion (or the first premise), since both give claims about what someone ŌĆśshouldŌĆÖ do. That makes the argument self-undermining.

Submodule 2.2 Quiz

Licenses and Attributions

Key Sources:

- Watson, Jeffrey (2019).┬ĀIntroduction to Logic. Licensed under: (CC BY-SA).

Next Page: 2.3 Realism