15.3 Individual Freedoms and Responsibilities

Students of logic have the opportunity to reconsider biases that say that we ourselves, our present time, and the way our world happens to be, are especially privileged over other people, times, or ways things could be.

15.3.1 Fairness

Self-serving bias may be widespread, but reason rejects a double standard.

Fairness: Avoiding Double-Standards

A basic principle of fairness is that we should only act on, and enforce, those rules which we could wish to be followed generally, not only in our own particular case. For instance, if everyone were to generally follow the rule to tell lies, then everything everyone ever said would be false; but in such a world, nothing anyone said would be accepted as true either, and so language would cease to mean anything, and lying itself would become impossible. Since the rule “tell a lie” leads to a contradiction when generally followed, one shouldn’t lie. Similarly, if nobody ever repaid money they borrowed, then “borrowing” would just be taking, but then nobody would ever be able to lend anything, and so borrowing would be impossible. So, one should pay back what they borrow. Again, if someone steals something, then they simultaneously act as if there is no private property (they ignore someone else’s ownership of property), and also that there is private property (they treat what they stole as though it were their own property). So, it is wrong to steal. Not to belabor the point, but suppose that everyone were to generally act on the rule, “kill people”. Everyone would then be dead, meaning that nobody could kill anybody, which contradicts everybody killing everybody. So, it is wrong for people to kill other people, at least as a general rule.

Again, if someone is distributing slices of pie, and they give a larger slice to one person, then consistency would require giving a larger slice to everyone, which would be impossible, because there wouldn’t be enough pie left. So, all other things being equal, you should divide up the pie equally. Of course, if someone baked the pie, then it would unfair to give them a slice of the same size as everyone else, since if pie-bakers only got as much pie as others, they’d simply stop baking pies, but then there would be no pie for anybody. This is the notion of fairness. Fairness means that, if the same reasons apply in each case, the same rules apply.

Reason rejects a double-standard. A “double standard” is a case in which a standard is not applied generally, but instead one standard is applied for one group of people, and another standard for another group, arbitrarily. It isn’t a “double standard” to, say, apply one set of rules to toddlers and another to adults: we don’t allow toddlers to drive, carry firearms, sign contracts, or vote. The same is true of people with severe mental impairments. It would be a double standard, on the other hand, to prohibit one group of equally competent adults from driving, carrying firearms, signing contracts, or voting.

Self-Serving Bias

Even though we all know reason rejects a double-standard, and get very angry when we see somebody else applying a double-standard we all routinely and thoughtlessly apply a double-standard when it comes to the most special person in the world: that is, ourselves. We hold ourselves to one standard, and all other people to another standard. Psychologists call this well-documented phenomenon self-serving bias, and one textbook describes it in this way:

- Self-serving biases are those attributions that enable us to see ourselves in favorable light (for example, making internal attributions for success and external attributions for failures). When you do well at a task, for example acing an exam, it is in your best interest to make a dispositional attribution for your behavior (“I’m smart,”) instead of a situational one (“The exam was easy,”). The tendency of an individual to take credit by making dispositional or internal attributions for positive outcomes but situational or external attributions for negative outcomes is known as the self-serving bias (Miller & Ross, 1975). This bias serves to protect self-esteem. You can imagine that if people always made situational attributions for their behavior, they would never be able to take credit and feel good about their accomplishments.

- Consider the example of how we explain our favorite sports team’s wins. Research shows that we make internal, stable, and controllable attributions for our team’s victory (Grove, Hanrahan, & McInman, 1991). For example, we might tell ourselves that our team is talented (internal), consistently works hard (stable), and uses effective strategies (controllable). In contrast, we are more likely to make external, unstable, and uncontrollable attributions when our favorite team loses. For example, we might tell ourselves that the other team has more experienced players or that the referees were unfair (external), the other team played at home (unstable), and the cold weather affected our team’s performance (uncontrollable).

Self-serving bias leads us to excuse ourselves when we do something wrong, but refuse to excuse others. We assume our good actions reflect our virtuous character, while our bad actions are just mistakes; whereas when we evaluate others, we assume their bad actions reflect their character defects. Self-serving bias makes us assume we have divided the pie fairly, even when we actually divided it up to our own advantage. A classic example of self-serving bias can be observed in roommates or housemates: each roommate assumes that they are doing a majority of the work keeping things up, and that the other roommate is the lazy one responsible for most of the mess. This is because each roommate sees only their own work and the other roommate’s failures, but is blind to the work of the other roommate, or to their own failures.

In logic, self-serving bias leads us to assume that we are the ones who are being rational, and our opponents are the ones who are irrational. It enables us to see all the fallacies in someone else’s work, but miss all of our own fallacies. The self-serving bias might be inevitable, but becoming a better reasoner means trying to recognize your own fallacies in reasoning, and to be more tolerant of the mistakes others make in reasoning: because you probably make them too.

15.3.2 Perspective

Neither novelty, nor tradition, nor the status quo are inherently better.

Perspective: Keeping History in Mind

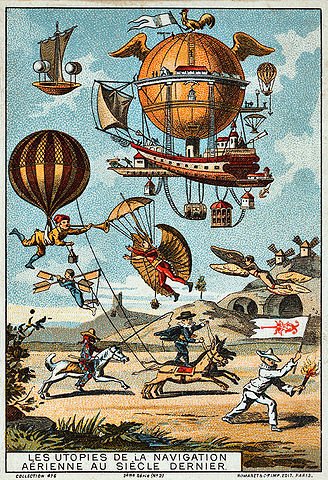

Having a historical perspective helps us see that there is no special privilege enjoyed by the way things currently are, and similarly no special privilege to something being very old or very new. Although this hasn’t been a history course, it should have made clear that there is nothing especially “logical” about one period of time over another: logic has been studied since even before Aristotle, and people have been committing fallacies equally as long. Studying logic can help free up someone’s thinking from the limitations of the era in which they find themselves.

Three common fallacies give priority to time: Appeal to Tradition, Appeal to Status Quo, and Appeal to Novelty.

Appeal to Tradition

Kip Wheeler defines “Appeal to Tradition” in this way:

- This line of thought asserts that a premise must be true because people have always believed it or done it. For example, “We know the earth is flat because generations have thought that for centuries!” Alternatively, the appeal to tradition might conclude that the premise has always worked in the past and will thus always work in the future: “Jefferson City has kept its urban growth boundary at six miles for the past thirty years. That has been good enough for thirty years, so why should we change it now? If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.” Such an argument is appealing in that it seems to be common sense, but it ignores important questions. Might an alternative policy work even better than the old one? Are there drawbacks to that long-standing policy? Are circumstances changing from the way they were thirty years ago? Has new evidence emerged that might throw that long-standing policy into doubt?

To be clear, the endurance of a tradition is evidence that the tradition is sustainable; unsustainable practices don’t survive for very long as traditions. A way of life which requires massive amounts of energy from non-renewable fuel sources will survive only as long as the fuel supply. We know which foods are safe to eat, and which will make us sick, mostly on the basis of tradition: if people have been eating it for centuries, bleu cheese probably won’t kill you. At the same time, sustainability is a necessary condition, not a sufficient condition, for being a practice worth keeping. There are other factors which need to be considered. Some traditional practices have survived despite being very harmful to people; some “traditional medicines” are ineffective or even harmful.

Appeal to Status Quo

The Status Quo is the way things presently are. For instance, the status quo for Puerto Rico is that it is neither a U. S. State nor an Independent nation, but instead an organized Territory of the United States. Just like appealing to tradition, appealing to the status quo goes too far. The fact that something is the status quo is evidence that there exist reasons why it is the way it is: otherwise, it wouldn’t be this way. It isn’t evidence that those reasons are as strong or as good as the reasons there might be to change the status quo. Owen Williamson describes appeals to status quo as cases of “Default Bias” and as the “Argument from Inertia”:

Default Bias. The logical fallacy of automatically favoring or accepting a situation simply because it exists right now, and arguing that any other alternative is mad, unthinkable, impossible, or at least would take too much effort, expense, stress or risk to change. The opposite of this fallacy is that of Nihilism (“Tear it all down!”), blindly rejecting what exists in favor of what could be, the adolescent fantasy of romanticizing anarchy, chaos (an ideology sometimes called political “Chaos Theory”), disorder, “permanent revolution,” or change for change’s sake.

The Argument from Inertia. The fallacy that it is necessary to continue on a mistaken course of action regardless of pain and sacrifice involved and even after discovering it is mistaken, because changing course would mean admitting that one’s decision (or one’s leader, or one’s country, or one’s faith) was wrong, and all one’s effort, expense, sacrifice and even bloodshed was for nothing, and that’s unthinkable.

Appeal to Novelty

The most common appeal which privileges one particular time over others, however, is not the appeal to tradition or status quo, but the appeal to novelty. The appeal to novelty argues that because something is new, such as a new product, new discovery, or new idea, the thing is better or more likely to be true.

Of course, it is true that newer products on the market tend to have improvements over older products, at least from the perspective of consumers, since they have to compete with older products. It is also true that newer technologies are able to build on older technologies, and thus newer computers tend, for instance, to have faster processors and more intuitive interfaces than older computers. Similarly, newer ideas often build on older ideas, and so scientific and intellectual progress is possible as we add to the knowledge we have over time. Newer theories have the advantage of hindsight, seeing how the older theories failed, and so, in a sense, the future is always “older and wiser” than the past.

Again, however, mere novelty is not enough to justify the claim that something is better or more likely to be right. Newer products are often made cheaper and more disposable while trying to emulate older products. New drugs may have long-term side effects that no one has had an opportunity to study, while the side-effects of older drugs are well known. Similarly, new ideas and novel claims haven’t had time to be put to the test, and their flaws identified. The older theory, while it may have many flaws, may turn out to be better than the newer theory, whose flaws having been discovered yet. Appeals to novelty can give the illusion of progress, when in reality an older, rejected idea has simply returned in fresher packaging. So, it is important for a student of logic not to be taken in by an appeal to novelty.

15.3.3 Imagination

Logic makes it easier to conceive of another way the world could be.

Imagination: How Things Might Have Been

Most students who start studying logic are surprised by the importance of other possible worlds in our definition of validity. We are accustomed to considering only (what we take to be) the actual world, the world in which we live and which we experience, when evaluating whether something is true or false. As we have seen, however, we need to have an understanding of what could be or could have been, as well as an understanding of what is, in order to evaluate arguments and practice sound reasoning. An argument with true premises and a true conclusion might still be invalid, if the conclusion could have been false in a world where the premises are true.

We have looked at a variety of ways to test whether or not an argument is valid, including truth tables, venn diagrams, and rules of inference. We’ve studied the rules for a variety of propositional connectives (and, or, if_then) and the rules specific to Categorical Syllogisms. We’ve looked at how to extract valid arguments, and how to evaluate the premises of an argument. All of this is the result of our desire to have a conclusion that isn’t a non-sequitur, that genuinely follows from the premises.

Because many of the tools we have studied are fairly rigid tools, designed to give us unambiguous answers about the validity of an argument and to make reasoning clear and explicit, some people associate logical thinking with rigid, uncreative thinking. This shouldn’t be the case, however. Because logic opens up the notion of how things might possibly be, beyond how they happen to be or how we currently expect them to be, the student of logic can be open to more creative and more imaginative thinking. It is no coincidence that philosophical themes play a role in a lot of science fiction and other imaginative writing: telling a story is narrating how things might be in another possible world.

Philosophy is sometimes criticized as a discipline for being impractical when it comes to pressing concerns, like the need to design better systems or to address the injustice in the world around us. Hopefully, through this course you’ve seen why this is not the case. In fact, much of what limits our ability to improve and address problems with the society around us comes from the same intellectual vices we started the course by studying: hubris, bias, wishful thinking, impatience, and a lack of interpretive charity and civility.

Hopefully, at the very least, the reader of this text is able to take away from the course a picture of how our arguments with one another might have been different than they are: an ability to imagine, at least, a better possible world, in which reason was the guide to human action.

Submodule 15.3 Quiz

Licenses and Attributions

Key Sources:

- Watson, Jeffrey (2019). Introduction to Logic. Arizona State University. Copyright 2019. Licensed under: (CC BY-SA).

Congrats on finishing the course!