15.2 Epistemic Freedoms and Responsibilities

Studying logic brings a number of freedoms and responsibilities in the beliefs one forms. This includes applying critical judgment by rejecting claims which, even if they canÔÇÖt be proven false, are not necessary to explain anything known to be true. It includes the freedom to be intellectually curious, and the responsibility to insist on deeper and more comprehensive explanations. It includes the freedom to change oneÔÇÖs mind, and the responsibility to do so when appropriate.

15.2.1 Critical Judgment

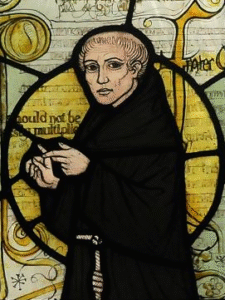

William of Ockham (1235-1347), for whom “Ockham’s razor” is named

OccamÔÇÖs Razor

Earlier, we discussed the principle of ÔÇťOccamÔÇÖs RazorÔÇŁ, that, when two explanations are equal in all other ways, the simpler of the two explanations is to be preferred. When both explanations equally fit with the evidence we have, and both explanations are equally good at predicting or explaining what we observe, the way to break the tie is to prefer the simpler explanation.

There are two good reasons to let OccamÔÇÖs Razor break the tie. First, inductively, we live in a world that seems in general (though not always) to be a place where events generally donÔÇÖt have extra, redundant explanations. When your car gets a flat tire, thereÔÇÖs typically one cause of the flat tire (say, a nail) rather than two, equally sufficient, independent causes (a nail and a screw). Sometimes our world contains ÔÇťcausal overdeterminationÔÇŁ, as in the case of a firing squad where each soldierÔÇÖs bullet is enough to carry out the execution, but this typically only happens as a result of coincidence or intentional planning. Second, the rules of probability tell us that the probability of two independent events A & B is always less than the probability of either event by itself. So, the more complex an explanation is, the less probable the explanation, all other things being equal.

OccamÔÇÖs Razor is not a rule of logic, however, but a ÔÇťrule of thumbÔÇŁ for practical judgment. It has to be applied carefully. Simplistic explanations, which lack the virtue of comprehensiveness and fail to explain as much as other explanations, are not typically the best explanations. For instance, it is ÔÇťsimplerÔÇŁ to say that the flat fire lost air randomly, for no reason at all, rather than that there was some nail or other puncture, but this wouldnÔÇÖt fully explain the flat tire.

Critical Judgment and Three Explanatory Virtues of Simplicity

Studying logic brings with it the freedom, as well as the responsibility, to apply critical judgment by rejecting claims which, even if they canÔÇÖt be proven false, are not necessary to explain anything known to be true. There are three virtues which explanations can have that all relate to OccamÔÇÖs razor. Van Cleave (2016) describes these three virtues:

Simplicity: Explanations that posit fewer entities or processes are preferable to explanations that posit more entities or processes.

Modesty: Explanations should not claim any more than is needed to explain the observed facts. Any details in the explanation must relate to explaining one of the observed facts.

Conservativeness: Explanations that force us to give up fewer well-established beliefs are better than explanations that force us to give up more well-established beliefs.

Van Cleave gives some examples of explanations which clearly violate one or more of these virtues:

- Bob explains the fact that he canÔÇÖt remember what happened yesterday by saying that he must have been kidnapped by aliens, who performed surgery on him and then erased his memory of everything that happened the day before returning him to his house.

- Mrs. Jones hears strange noises at night such as the creaking of the floor downstairs and rattling of windows. She explains these phenomena by hypothesizing that there is a 37-pound badger that inhabits the house and that emerges at night in search of Wheat Thins and Oreos.

- Edward saw his friend Tom at the store in their hometown of Lincoln, Nebraska just an hour ago. Then, while watching the World Cup on television, he saw someone that looked just like Tom in the crowd at the game in Brazil. He hypothesizes that his friend Tom must have an identical twin that Tom has never told him about.

- Elise has the uncanny feeling that although her family members look exactly the same, something just isnÔÇÖt right about them. She hypothesizes that her family members have been replaced with imposters who look and act exactly like her real family members and that no one can prove that this happened.

- While walking through the forest at night, Claudia hears some rustling in the bushes. It is clear to her that it isnÔÇÖt just the wind, because she can hear sticks cracking on the ground. She hypothesizes that it must be an escaped zoo animal.

- While driving on the freeway, Bill sees the flashing lights of a cop car in his rear view mirror. He hypothesizes that the cops are going to pull someone over for going 13.74 mph over the speed limit.

- Stacy cannot figure out why the rat poison she is using is not killing the rats in her apartment. She hypothesizes that the rats must be a new breed of rats that are resistant to any kind of poison and that evolved in the environment of her apartment.

For each of these purported explanations, you should be able to recognize a simpler, more modest, or more conservative version of the same explanation. For instance, the cop car that Bill sees in his rear view mirror might be pulling over someone for speeding, but not necessarily for going precisely 13.74 mph over the speed limit. The sound Claudia hears in the forest at night might be an animal, but not necessarily an escaped zoo animal.

15.2.2 Curiosity

Baruch Spinoza (1632-1677), who accepted the Principle of Sufficient Reason

Curiosity: Always Looking for Better Explanations

Intellectual curiosity is the virtue of never being satisfied with the limits of what one currently knows, but always looking for a better understanding of the world and a more comprehensive picture of why things happen as they do. ÔÇťJust becauseÔÇŁ is not a satisfactory answer for an intellectually curious person. Studying logic ought to enable someone who is intellectually curious to more freely pursue their interests. It also brings with it a responsibility to be the person in a group who insists on not settling for a simplistic or inadequate explanation.

Things in our world tend to happen for general, consistent, dependable reasons. When water in a pan evaporates, weÔÇÖre justified in assuming the water evaporated for a reason, and that this reason is something which would equally apply in similar circumstances, and is part of a more general principle. The water evaporated because of the hot, dry air outside, which is what water does, because of some general principles about state changes from liquid to gas and the diffusion of water vapor in air.

People often settle for explanations which are not comprehensive, explanations which fail to explain everything, or which either lack explanatory depth or lack explanatory power. Van Cleave (2016) describes these virtues in the following way:

- Explanatoriness: Explanations must explain all the observed facts.

- Depth: Explanations should not raise more questions than they answer.

- Power: Explanations should apply in a range of similar contexts, not just the current situation in which the explanation is being offered.

Examples

Van Cleave (148-149) offers these examples of explanations of a lack of power and a lack of depth, when attempting to explain why his car window is broken and his iPod is missing.

Suppose that when confronted with the observed facts of my car window being broken and my iPod missing, my colleague Jeff hypothesizes that my colleague, Paul Jurczak did it. However, given that I am friends with Paul, that Paul could easily buy an iPod if he wanted one, and that I know Paul to be the kind of person who has probably never stolen anything in his life (much less broken a car window), this explanation would raise many more questions than it answers. Why would Paul want to steal my iPod? Why would he break my car window to do so? Etc. This explanation raises as many questions as it answers and thus it lacks the explanatory virtue of ÔÇťdepth.ÔÇŁ

Consider now an explanation that lacks the explanatory virtue of ÔÇťpower.ÔÇŁ A good example would be the stray baseball scenario which is supposed to explain, specifically, the breaking of the car window. Although it is possible that a stray baseball broke my car window, that explanation would not apply in a range of similar contexts since people donÔÇÖt play baseball in or around parking garages. So not many windows broken in parking garages can be explained by stray baseballs. In contrast, many windows broken in parking garages can be explained by thieves. Thus, the thief explanation would be a more powerful explanation, whereas the stray baseball explanation would lack the explanatory virtue of power.

The Principle of Sufficient Reason

There is a metaphysical ÔÇťprinciple of sufficient reasonÔÇŁ, which is a controversial principle stating that every fact in the world has an explanation of some sort. Philosophers have long debated whether this principle is true. Less controversial, however, is what we might call the methodological principle of sufficient reason, or the idea that we shouldnÔÇÖt stop looking for explanations until the explanation we have is a sufficient condition of what it is supposed to explain. In other words, if we were to put our explanation in the premises of an argument, and the thing we hope to explain in the conclusion, then we should regard the task of explanation as ÔÇťcompleteÔÇŁ or ÔÇťfinishedÔÇŁ only when the resulting argument is valid, and the premises entail the conclusion. For instance, this explanation would be incomplete:

1. The air is hot and dry.

C. The water evaporates.

It is incomplete because the argument is, quite obviously, invalid. On the other hand, this explanation would be complete, because the resulting argument would be valid:

1. The air is hot and dry.

2. Anytime the air is hot and dry, and there is water, the water evaporates.

3. There is water.

4. The air is hot and dry and there is water. (1, 3 &I)

C. The water evaporates. (2, 4 MP)

The methodological principle of sufficient reason helps us understand why we search for powerful, general explanations (i.e., 2. Anytime . . . ) to accompany particular facts we observe: these general principles are necessary to make our explanations sufficient conditions of what they explain.

15.2.3 Change

Averroes (1126-1198), author of “The Incoherence of the Incoherence”

Change: Updating Your Beliefs

You have the freedom to change what you think about something, and also the responsibility to do so when appropriate. Whenever you get new evidence, you should update your beliefs in light of the new information. Perhaps your beliefs stay the same, but they become more certain, or less certain, than they were before; or perhaps you change your mind entirely.

Surprisingly, many people do not change their minds, even when presented with new evidence. There are many reasons for this, but three related reasons are cognitive dissonance, motivated reasoning, and the sunk cost fallacy.

Cognitive Dissonance

Cognitive dissonance occurs when we find ourselves simultaneously holding two beliefs or attitudes which are in conflict with each other. The beliefs could be logically inconsistent and contradictory, such as a belief that oneÔÇÖs spouse always tells the truth, and the belief that oneÔÇÖs spouse has knowingly said something false. Both beliefs cannot be true in the same possible world. Often, however, the beliefs or attitudes which cause cognitive dissonance are logically consistent, and could both be true, but they still seem to be in conflict or tension with each other. For instance, somebody might generally trust a particular news anchor, but then learn that the news anchor has reported an internet meme as though it were a news story. Somebody might generally hold politically liberal attitudes, but then find themselves upset with a specific government program that was justified on politically liberal grounds. Somebody might generally hold a religious outlook, but find themselves disagreeing with public statements by their co-religionists. Somebody might trust a brand to provide great coffee, and then have a terrible cup of coffee.

Cognitive dissonance is uncomfortable, and we naturally strive for beliefs which seem more consistent and coherent. So, what people generally do is try to reject some of their evidence in order to drop the weaker of the two conflicting beliefs. For instance, when the trusted news anchor reports an internet meme as a news story, the person may decide they never really trusted the news anchor all along, or that the internet meme is in fact true and newsworthy despite evidence to the contrary.

A student of logic, however, is able to distinguish contradictory beliefs, such as the belief that P & ~P, from beliefs which are merely in tension with each other. The student of logic knows to reject at least one of two contradictory beliefs, but also knows that the truth can often be complex and nuanced. A trustworthy journalist can still make mistakes. A particular public policy can be bad without undermining an entire political theory. Someone can mess up a cup of coffee. Studying logic helps with seeing how conflicting beliefs are not always contradictory, and becoming more comfortable with holding beliefs which are in tension with each other.

Motivated Reasoning

Unfortunately, what happens most of the time is that people fall from cognitive dissonance into motivated reasoning, where the desire to preserve one of their more central beliefs leads them to simply reject evidence or information which seems to be in conflict with that belief. For instance, a politically liberal person will reject any evidence that seems to support a politically conservative position, or a political conservative person will reject any evidence that seems to support a politically liberal position. Instead of basing beliefs on all of the evidence, motivated reasoning leads people to limit themselves to evidence that supports their existing basic beliefs. Emotions are often a factor in motivated reasoning: beliefs are closely intertwined into how we live our lives, and a challenge to those beliefs is a challenge to how we live our lives, which can feel like an emotional threat. To avoid these feelings, people ignore evidence that doesnÔÇÖt support what they already think to be the case.

Sunk Cost Fallacy

A particular form of motivated reasoning is the sunk cost fallacy, where the desire not to have been wrong all along leads someone to reject changing their minds. The example comes from economics. Suppose that you have invested in a business. The business is now failing, and needs more investment to survive and make a profit. You could invest in saving the old business, which will likely bring a profit. Or you could use the same amount of money to start a new business, which would be even more profitable. The rational choice (assuming all else is equal) is to let the old business die and to start a new business; but in practice, the feeling the initial investment was ÔÇťwastedÔÇŁ leads people to pour money into the failing business. You might have encountered the sunk cost fallacy when, a couple weeks through a class, you realize the class has been absolutely miserable. Instead of withdrawing from the class and taking one you enjoy, you might choose to stick it out in the class so that your prior misery wasnÔÇÖt ÔÇťwastedÔÇŁ, even though this means even more misery for you ahead. Gamblers are especially prone to the sunk cost fallacy: instead of walking away from a bad hand, they may ÔÇťdouble downÔÇŁ on their bets in the hope of winning back their losses.

In terms of reasoning, the sunk cost fallacy causes us to ÔÇťdouble downÔÇŁ on our prior beliefs instead of re-evaluating them in the light of new evidence. For instance, someone who has spent many years and a lot of effort claiming that something is true, or that some policy is the right policy, may feel as though they donÔÇÖt have the freedom to change their mind anymore: they feel it would be inconsistent, and make a mockery of all of their past efforts.

The more practice one gets in thinking slowly and practicing sound reasoning, the more easily they can recognize when they are falling into one of these errors.

Submodule 15.2 Quiz

Licenses and Attributions

Key Sources:

- Watson, Jeffrey (2019). Introduction to Logic. Licensed under: (CC BY-SA)

- Andrea di bonaiuto, apotesosi di san tommaso d’aquino, 11 averro├Ę by Sailko, under license CC BY-SA 3.0.